Tech companies are not your friends

There has been a great deal of debate in recent years about finding a balance between privacy and security. What we talk about far less, however, is the balance between privacy and convenience.

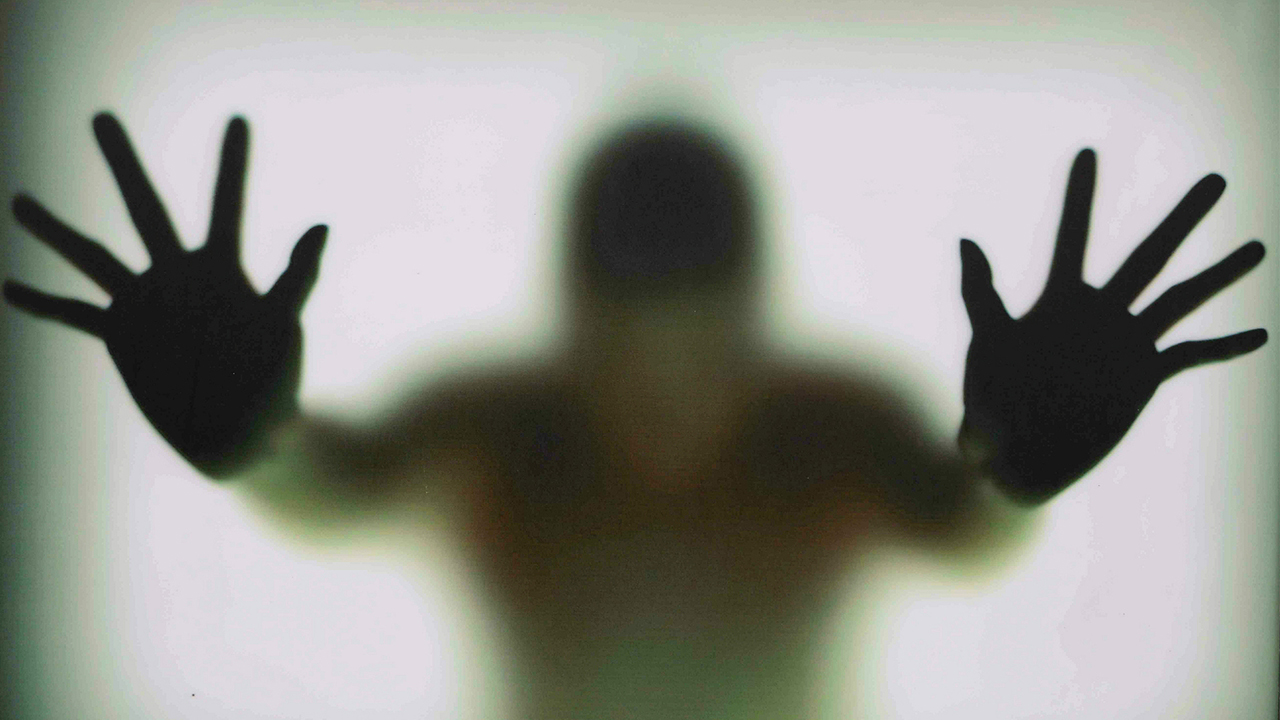

We are living in the most surveilled era in human history. The amount of information which is captured, recorded and analysed about each of us on a daily basis surpasses even the wildest dreams of the Nazi Secret Police or the Soviet KGB.

Unlike previous surveillance states, however, at least for those of us in the West the majority of this surveillance has not been imposed on us from above by a dictatorial regime, nor is it held in place by the threat of government violence. Instead, we are willing collaborators with a host of corporations and tech companies in constructing a society in which almost all of us are being watched, almost all of the time, not for political control but for private profit. We are voluntarily turning ourselves into the objects of constant surveillance, and we are doing it all for the sake of a little extra convenience.

But is the sum of the many small choices we make – to save a few minutes here, a few dollars there – adding up to a society which we want to live in?

A cage, after all, can be a very convenient place to live.

How many companies know where you are as you read this article? It’s likely more than you think. Could you even venture a guess about how many know where you live, where you work or what you bought last week?

We have invited a vast array of data-driven technologies into our lives on the basis that they are convenient. Between our smartphones, our electronic payments, our social media use, our Google searches, our Uber rides, our Spotify accounts, our Fitbits and any one of the myriad other services we use to make our lives run that little bit more smoothly, there is almost no moment in the day where one company or another is not collecting some form of data about us. As a society we have literally bought into the idea that constant, ubiquitous surveillance is an acceptable price to pay to make our lives more convenient.

Part of the issue is that we are very bad at weighing up the relative value of the service provided to us in comparison to the data we are giving in exchange.

Take the Zomato app for example. In ordering food through the app, instead of using the same phone to call and place an order, you might save yourself a few minutes and a phone call. In return, however, a company which is not actually providing the food and did not need to be involved in the transaction is granted access to your phone's location (both GPS and network-based), your contact list, your text messages, the contents of your USB storage, your camera, your device ID and full network access. Even if you read the privacy policy before clicking ‘accept’ (which, let’s be honest, nobody does) you still can’t find out exactly which companies Zomato is sharing your information with, let alone which companies those companies are sharing your data with, and on and on.

The surveillance society we are helping to build is a one-way mirror. The network of data collection and data sharing remains opaque to us, even as we allow our lives to become ever more transparent to it. We allow this without thinking too much about it, because the benefits seem obvious and immediate, and the costs far off and intangible.

This is not an accident; it is a design principle. Removing “friction” for users is a core goal for the designers of these digital services. They want their products to move you as swiftly and smoothly as possible from one end of the transaction to the other. Friction in this context is anything that disrupts that seamless experience – and gives you a reason to stop and think about whether you really need to buy another pair of pants or sign up for an app which monitors how much water you drink.

Companies don’t collect your data because they’re your friends. They collect it because they intend to make money off you, even if you can’t immediately see how. It may be something as straightforward as serving you targeted advertising, or as complex as selling your data through a web of data brokers to third parties like insurance companies and credit agencies. Data that you give away to a fitness app to more easily track your exercise could end up being used to decide how much you pay for health insurance.

The sum of small choices shape the society we live in. The little decisions which we make for the sake of convenience – to turn on location tracking to use the delivery app, to enable facial recognition because remembering a password is too difficult, even to allow the government to manage our medical records – are adding up to create the most heavily surveilled society ever to exist, without anyone (except the companies, perhaps) actually having intended to do so.

We are rapidly approaching a point at which the phrase “the walls are listening” will no longer be metaphorical. The coming wave of internet-enabled home devices like Google Home and the Amazon Echo will greatly expand the capacity for surveillance into every nook and cranny of our lives, blurring the distinction between online and offline data collection.

And once we’re on the hook, we’re often hooked for good. The thing about convenience is that it often turns into dependence. A decade ago, barely anyone owned a smartphone; now many of us are all but inseparable from them. It is likely the same will apply to the approaching tsunami of smart home devices. That’s why it’s important that we think about what we really want from these machines before we bring them into our homes.

This is not an argument against the use of convenient technologies. It is, however, an argument for recognising that we have choices about how we integrate these technologies into our lives, and that those choices have consequences for the society we live in.

We are at the crossroads to creating a highly convenient dystopia, and we have a choice which road we go down.

Before downloading that app or signing up for that service, we need to stop and think critically about the kind of future we’re building, and how much we’re willing to give away in return for a more convenient way to turn the lights on. We need to make sure that the balance of power rests with how we want to use technology, rather than how our technology is using us.

Elise Thomas is a Melbourne-based freelance journalist with an interest in humanitarian and human rights issues and the impacts of new technologies. She has studied international affairs at the Australian National University and the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.

This article was commissioned as part of a series for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, 2018.