Sean Turnell: An Unlikely Prisoner

I’m someone who never even got a parking ticket – an academic – and suddenly I'm in with drug traffickers, fraudsters, kidnappers, murderers. It's going to sound very odd, but most of them were very, very nice.

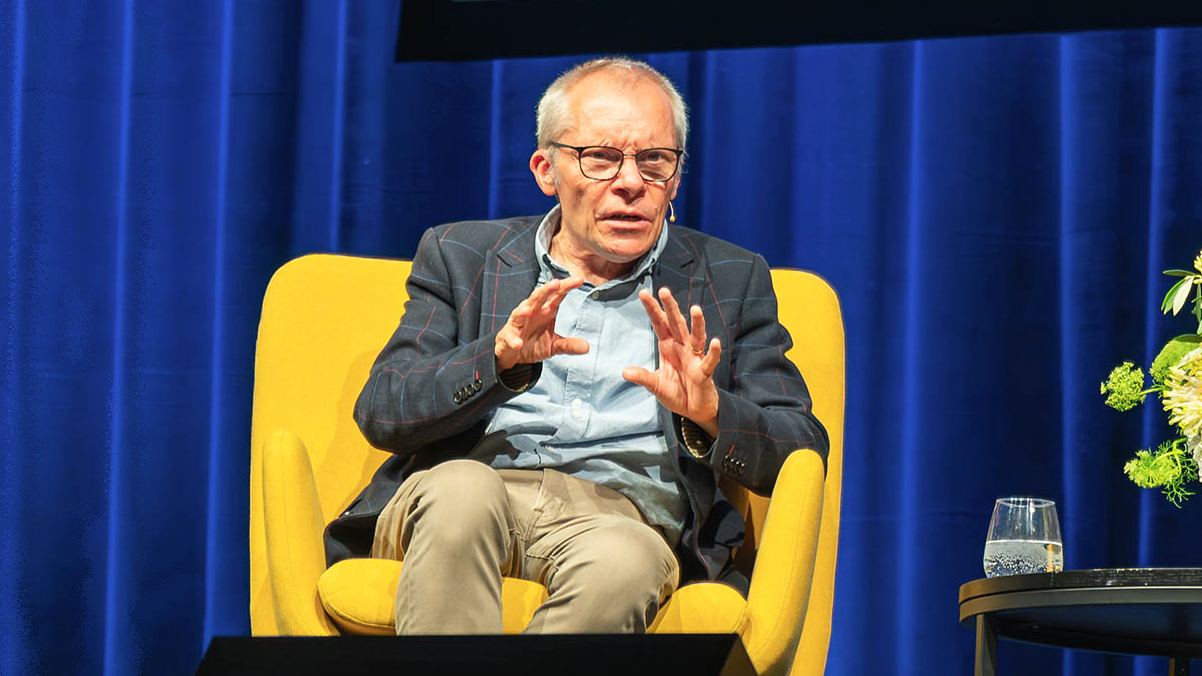

In the wake of the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, Sean Turnell was held for 650 days in Myanmar’s terrifying Insein Prison on the trumped-up charge of being a spy. His improbable story as an optimistic economics professor unfolds in his book, An Unlikely Prisoner, where he recounts how he survived his traumatic incarceration.

In conversation with Melissa Crouch, a UNSW Sydney Professor who was part of the team advocating for his freedom, Sean shares how he not only survived his lengthy and traumatic incarceration, but also left with his sense of humour intact, his spirit unbroken and love in his heart. Sean's unique perspective coupled with his expertise on Myanmar offers broader insights into the plight of the people and the political prisoners under Myanmar’s newest dictators, and the many human rights issues at play.

Transcript

Centre for Ideas: UNSW Centre for Ideas.

Melissa Crouch: Good evening and welcome. Let me begin with an Acknowledgement of Country. I'd like to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land, the Bidjigal and Gadigal Peoples of the Eora Nation, and pay my respects to Elders past and present, and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are present here tonight. Welcome to tonight's discussion with Professor Sean Turnell about his new book, An Unlikely Prisoner.

We live in difficult times of war in many parts of the world; Ukraine – Russia, Israel – Hamas and Myanmar's military and its own people. The war in Myanmar is not well known, and yet deserves our attention, particularly due to its proximity in Australia. In brief, on the 1st of February 2021, the military staged a coup, disrupting ten years of reform. In figures, the situation has been stark. 25,000 people have been arbitrarily detained – one of whom was Sean – and 19,000 of those are still under detention. Many are doctors and nurses, civil servants, students, artists, among others. It's estimated by the AAPP that around 4,100 civilians have been killed. Further, the military recommenced the death penalty, with four killed in 2022. To give you an idea of the scale, and escalation of the conflict just over the past year; in September this year, the UN condemned the intensification of airstrikes by the military against its own people, and there was recognition of at least 22 instances of mass killings. These are difficult statistics to digest. But we have with us Sean tonight, to share his experiences of being detained in Myanmar for 650 days, from the 6th of February 2021 to the 18th of November 2022. How we might ask, is it possible to cope with the suffering and pain in Myanmar? How do we sustain hope in tragedy? This is the question we want to look into today.

So, Sean, welcome. Your book starts with the story of your arrest. Tell us, how did you, an Australian economist from Western Sydney find yourself under arrest in Myanmar?

Sean Turnell: Well, it's a very long story, if one goes back to the start. But I got to know many people in the Burmese community here in Australia, so I worked with them and helped them critique past military regimes. But for me, it was always from the economics, and I got to know many people. Eventually my whole academic career went towards Myanmar as well, and I wrote a book on the history of the country's financial system. Which bizarrely, was then turned into, like, a radio play, which was broadcast by the BBC Burmese service, and one of the people listening to that was Aung San Suu Kyi, whilst under house arrest. And so when she was released in 2010, we got in contact, began a correspondence, then when she was released, I met her. But yeah, it's basically a story which began with sharing a house with some Burmese people, and then just sort of a deepening academic, sort of relationship, and then finally ending up after the elections of 2015 when Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy won the election. Daw Suu said to me — as Aung San Suu Kyi is known — said to me on the day after the election, Sean, ‘Why don't you come over and give us a hand?’ So I got the support of Macquarie Uni, the Australian Government, and yeah, ended up over there. So…

Melissa Crouch: Take us to the day of the arrest. So we had the coup on the 1st of February, you were there in Myanmar, and then, the 6th of February you find yourself under arrest. Tell us a bit about those circumstances.

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So it was very odd. And Melissa, as you said, the coup took place on the 1st of February. And at first I wasn't too worried, for a few reasons. Number one, and it's hard to think about it now, but, there really were thoughts that this would end. That it wouldn't last, because it didn't make any sense. Well, it still doesn't make any sense, but it didn't make any sense, and we thought that maybe it would end. And also, as a sort of fairly high profile foreigner, I thought they'd leave me alone and so on. But then gradually it became apparent that, you know, I really needed to get out. And I tried to get out, but of course this is the middle of COVID, so there were no scheduled flights or anything like that. To be honest, I was probably a little bit complacent, but also had a very strong feeling too, which again, in retrospect is a bit foolish, but, thinking, not wanting to run away, when my Myanmar colleagues are all being rounded up. So I remember having that very strong feeling as well. So yes, I ended up being there, couldn't get out, and then on the 6th of February, I wake up to this email saying that military intelligence and the police have taken over the security system of the hotel, and it was time to get out. And I tried to get out, but of course, by that time it was way too late.

Melissa Crouch: So your arrest was fairly high profile. I think you even mentioned in the book, you were actually on the phone to journalists /

Sean Turnell: I was.

Melissa Crouch: / and others in the process of being /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / arrested by a sort of large group of people over a number of hours. And it was also fairly clear that your arrest was, perhaps, symbolic and unusual. Tell us about what the hotel staff did as you were leaving the hotel. So you had your laptop confiscated, your phone confiscated, you knew things were going downhill, the ambassador hadn't been able to… hadn't been successful in the negotiations. They were taking you away in a van to who knows where. What did the hotel staff do?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, I mean, the hotel staff were firstly, they were mortified that this was happening, because I'd got to know the hotel staff over a long period of time. But yes, specifically what they did, as I was being taken away and put in the police van, all the staff and I mean all the staff, from the kitchen, all the people, who clean the bedrooms, all of them, everyone just came out on the driveway to wave goodbye. Many in tears, and many doing that… the three fingers, sorry this is a bit rude that way, the three fingered symbol from The Hunger Games, right? Which is increasingly used across Asia. So yeah, but incredibly brave and very much let the police know that this was appalling and shouldn't be done. Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: So where did they take you to after that?

Sean Turnell: So the first time… the first place they took me to was to Tamwe Police Station. So for people who know Yangon, it’s just a police station, and, you know, part of the city. It was interesting going there, because, of course, by this time, so, we're five days after the coup, the protests are really beginning to rise up. And so I could hear the protesters, as they’re walking past Tamwe Police Station, and I’m inside. And they were singing out to me, which I thought they were at the time, and then later found and actually when I met some of them that they did. That was okay! The worst thing happened then in the middle of the night. So at about one or two a.m in the morning, I was taken from Tamwe Police Station north west in the city, and it was tantalising actually, because, of course, there are two big places north west of Yangon. One is the airport, and one is Insein Prison. And I'm thinking as we're going along, the mixture of hope and fear, and thinking, they’re taking me to the airport, I'm just going to be put on a plane and booted out of the country, or they’re taking me to the prison. And it turned out they were taking me to a police station just outside the walls of the jail. And I was taken into this interrogation room, which in the book I called ‘The Box’. And I lived in that room for two months, and that room was very tiny, I think, you know, dominated by a chair, a metal chair with a leg… with chains from the leg of the chair, more chains from the armrests with hand, wrist manacles, and leg irons, and that sort of stuff. Like it was a horrific image. And there's no windows or anything like that, except a small slit one for the police to look in. Yeah. So it looked mediaeval. It looked just awful. And I slept in that, and lived in that, for two months.

Melissa Crouch: And I mean, initially nobody knew where you were, by and large, right? At this time. So you're taken to solitary confinement, effectively. Tell us a bit more about that, in terms of, your loss of sense of self control over the situation. You know, what were the sounds, the smells of captivity? How did you experience that?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, So I think that captures it, because the biggest thing you lose is any sense of agency. You've got no choice over anything. You've got no control when you sleep, when you wake up, when you eat anything, you're completely out of people's control. And for me in Myanmar, because Myanmar is an incredibly hospitable country, as you know really well, Melissa. So this is just so, out of, you know, any experience that I'd ever had before, or anything else. I mean, one of the jokes going around is that, I've never even received a parking ticket, which is true, for people who… I know there are people in this audience who’ve known me since I was five years old. I don't get into trouble. And there I am in this, you know, this box with, yeah, no control over everything. So, interesting enough, the first thing you try and do is assert control, in some way, over your environment, which we probably come to. But… yeah, and the sounds, unfortunately, it wasn't too long from that point before I heard prisoners being tortured nearby. So that was the bad sound. So good sounds, I could hear the protesters. I could actually hear the pots and pans being beaten and all that, and the crescendo as they approached the jail and then moved away. So…

Melissa Crouch: And I think you said that's, sort of, the only way you could tell time. So /

Sean Turnell: That’s right.

Melissa Crouch: / in Myanmar, people were banging pots and pans, /

Sean Turnell: Yep. Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / sort of, usually in the evening. /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / And that was the way that you were able to tell the time?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, Yeah, exactly. Because there was no natural light. So I didn't even know whether it was day or evening. And I think that suited the interrogators very well because they would like to come in the middle of the night, and ask questions. You'd be, you know, woken up, yeah. So, I think that's part of it, right? Keep you off balance.

Melissa Crouch: Tell us a bit more about those interrogations. Who interrogated you, about what, and about… did it make sense or was it complete nonsense?

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So, a bit of both. So at first it was complete nonsense. And then increasingly it became clear that they wanted to implicate Daw Suu and other government ministers, and all that. But but, but the questioning was always bizarre, always absurd, all the way through. And so I was accused of simultaneously working for MI6, George Soros, what was the other one? There were three that they accused me of working on… anyway. But George Soros and MI6 and um, but yeah, would present me with documents that I'd written myself, and I was asked, you know, how had I got this? And when one of the documents I said, ‘Well, you know, I actually wrote it’, and they said, ‘Well, it doesn't matter, you shouldn’t have read it!’ So I knew I was on the… beyond the looking glass then. But yeah, essentially just a, sort of, disoriented, but there were mostly three in the room and in the book I talk about the names that I gave them, and they're not very imaginative. The main interrogator was a guy who wore a leather jacket, and I call him Leather Jacket! So yeah, but… always two, sometimes three, with somebody wandering in behind you, which also, you know, puts you off balance as well.

Melissa Crouch: So, tell us a bit about some of the techniques that you used in The Box, in particular, to survive, /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / keeping in mind you weren't able to bring in anything with you. You knew when you were arrested… well, you sort of panicked when you were arrested /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / in the sense that you didn't have any reading materials, /

Sean Turnell: That’s right.

Melissa Crouch: / nothing to pass the time.

Sean Turnell: That was… yeah.

Melissa Crouch: So what did you do? How did you cope physically /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / and mentally?

Sean Turnell: Well, firstly, that terrible, terrible moment when I realised I had nothing to read. And again, I know that there are people in this audience who know what it's like when I don't have something to read. Yeah, so, but again, you sort of reassert some degree of control. So the first thing that I think all sentient beings do when they're confined, which is just to pace, up and down in whatever the surrounds you're in, and that gives you something to do. And just you know, it also keeps panic at bay. But I think also allied with it, is that I would count, so I would touch one wall, touch the other wall. I'd counted how many steps it was, in any case, it was eight steps, for the record, from one to the other wall. And then I'm trying to get the 10,000 step average every day. And it really did feel good, if I was at 12,000 or 13,000, I thought, yes! But yeah, but I think the counting was really important because again, it's a way I think we like to measure and categorise, and make sense of our environment - and I think that's part of it. But also, it stops you thinking, because you've got to remember where you're up to. So that was really critical. And then after that, I started inventing games as well, after the counting novelty had worn off. And I tried to remember, you know, every US president in chronological order, all the 50 states of the US… / I’m somewhat of an Americophile.

Melissa Crouch: / I won’t make you recite them now /

Sean Turnell: Indeed!

Melissa Crouch: / But it sounds like you certainly /

Sean Turnell: Yes I couldn’t do it now.

Melissa Crouch: / You recovered a memory… You recovered a… /

Sean Turnell: That’s right!

Melissa Crouch: / new sense of memory?

Sean Turnell: And that was a bit of an upside at the time. And since, maybe? Because before going in there, probably like, you know, I was 57, then, I’d begun to worry about early onset Alzheimer's, and, but my memory became this incredible thing, like savant-like, the things I could remember were extraordinary. And so, you know, the story of the US presidents, I remember, you know, Grover Cleveland's two separate terms and who was on the other side, and it was just astonishing. And all from things that, you know, I hadn't at all deliberately tried to remember. This was all just coming out of the attic that was my mind. So, yeah. So it was really interesting actually, that whole…

Melissa Crouch: But of course you had… it wasn’t all fun memory games /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / You had a lot of disruptions /

Sean Turnell: Right.

Melissa Crouch: / And I think that was part of the tactics /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / of those who were, who had you under their control. One of your chapters, I think, is called The Beheading. Tell us a bit about that.

Sean Turnell: Oh, the what?

Melissa Crouch: The Beheading. So this is…

Sean Turnell: Oh! Yes, sorry.

Melissa Crouch: You mentioned fears /

Sean Turnell: Yes, yes of course.

Melissa Crouch: / of being beheaded /

Sean Turnell: Yes.

Melissa Crouch: / at one point.

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So, about two weeks in, something like that, I was taken to another building on the campus, where Insein prison is. And they’d set up a studio! And what it was, because again, this is the middle of COVID, so they wouldn't let the embassy come to the prison, or in any way meet me in person the whole time, actually. But certainly at this early point. And so it was just a video hook up for Zoom! But I entered this room and all I could think of, when I saw this chair, and the video and some going in like army fatigues, behind the camera, all I could think of were those awful ISIS videos, right? Of people being beheaded. And I just thought, oh my god, like, I mean, I didn't really think I was going to be beheaded, but it was just a horrific scene. Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: So, in the book, you then turn back a bit to reflect on your time with the NLD government. So I thought it would be useful to come to that. And we've already talked a bit about how you're from Western Sydney, you're an economics professor, but also a bit of an amateur history buff, and you reflect on, sort of, your role as an economic adviser and the kind of model you aspired to be. So, who was it that you aspired to be like, as an economic advisor in Myanmar?

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So there was a few. There's a very famous oh, sorry, not very famous actually, in Myanmar he's quite famous, a guy called Louis Wallinsky, who was the chief advisor to Myanmar's first prime minister, who was deposed in a coup, also. A guy called U Nu. And Wallinsky, who I got to read his private correspondence and in writing, material on him. So he was there. Another quite… a famous economist called Albert Hirschman. For those, for all of us here in Australia, a man called Heinz Arndt. So there were a few of those people who it was not really for them just about economic reform. It was always economic reform for a reason. It was about lifting living standards and all that, but it was also about how to create a democratic and liberal society, and the interaction of those that a democratic liberal society is sort of the end that you're trying to achieve, but it's also part of the means of getting to prosperity and stability and things like that. So I very much modelled on what I… I've tried to model myself from what they were trying to do. But yeah, again, always with those objectives, because Myanmar had been left behind, is left behind by the other Asian tiger economy. So we were desperately trying to lift its economic performance, but we were also trying to create an economic system that was good for democracy, good for a liberal society. So we were going after some of the monopolies and so on. And all of that would cause us trouble later, as we found out.

Melissa Crouch: So this period, pre-COVID, 2011 to 2019, was, I think it's fair to say, a time of high optimism, to some extent. But how difficult was it for the NLD to actually implement reforms, and in many ways, to meet both local and international expectations of economic performance? Can you, sort of, give us a snapshot of the barriers, I guess, to economic reform and the challenges?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, it was really, really tough, and not just in the obvious ways, because it's difficult anywhere, right? To conduct economic reform. Economic reform is always controversial, there are always losers. So you're going to get blowback anyway. Probably the biggest shock for me… although, I’d spent nearly a decade at the Reserve Bank, so I had some exposure to bureaucracy and so on. But the bureaucracy in Myanmar was extraordinary, unmoving, top down, hierarchical, and yeah, getting things done was just ordinarily difficult. So you can have any number of really good ideas, or have, even political buy in, and so on. But to get things done, to get it through the bureaucracy is really tough. So it was a big struggle. It's something that, you know, we're able to reflect on after the event, of course, after the coup. Of just how we should have probably done some things differently. So, some of my thoughts went to that as well. But yeah, but I think the bureaucracy, number one, but then, as I say, the blowback from the entities who were harmed by these reforms /

Melissa Crouch: Military in particular?

Sean Turnell: Sorry?

Melissa Crouch: The military in particular?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, exactly. So, yeah. So, there's a lot of the military and the crony enterprises connected to it. We were getting threats at the time. In retrospect, I can see now that we didn't take it seriously enough. Ooh, sorry, I should say, I didn't take it seriously enough. But yeah, so certainly a bit of blowback there. And then I think in the international community, Myanmar suffered, and to some extent, well, yeah, it did suffer back then, with excessive expectations of what could be done, I think. Sort of, come from a good place, if you like, but that was problematic as well, because you were dealing with disappointed expectations, on top of, you know, these very real barriers to progress.

Melissa Crouch: And so the NLD won an election, and was about to take a second term of office. Let's just, sort of, indulge your economic nerd for a little bit longer. What was on the economic agenda for the second term?

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: You know, what… if they had been able to take office, what might have happened?

Sean Turnell: So this is what's so frustrating. I mean, there's so many things that are frustrating, but we're in a, quite a good place. Having said that, of course, this is the time of COVID. And so at that moment, we were sort of reorienting everything towards COVID recovery, and trying to deal with COVID. Again, it’s really funny to remember now, isn't it? Where… when COVID first hit, or a little bit after that, there was a widespread belief that the countries of Southeast Asia didn't really have much to worry about, young population, SAARS and all that. There was that belief that people were inoculated. And so, I remember that at first, didn't seem like it was going to be that serious. But then of course, it became serious. So, we were sort of shifting things towards that. But already, though, beginning to shift back, towards what could be done in the second term of the government. As you said, Melissa, the NLD, the National League for Democracy, had won a second term, and in that second term we were going to be much more adventurous, because in a sense the first term was doing that hard unpopular stuff, particularly around government spending, things like that. Again, some of the critical foundations, but in the second term was going to become some of the sexy stuff, frankly. Some of the, you know, increased spending on health and education and infrastructure. Had all sorts of plans, yeah, to really accelerate the reform process, but also, to go even stronger against the military enterprises and these crony firms as well. So… and so you could feel the tempo of resistance beginning to rise as we were doing that as well.

Melissa Crouch: So let's come back to the book, and after reflecting a bit on your time advising the NLD, you then speak about how you were moved from The Box, so from solitary confinement, to Insein prison. So tell us a bit about Insein prison. I think some of us perhaps have heard of this infamous prison in Myanmar, in Yangon, in particular. Is it as bad as it sounds?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, in a way, I think yes, it is. So people who have seen the book, will have seen the photograph. But Melissa, you would know it, anyone who has been to Myanmar will know it, because as you leave Yangon Airport, it's directly below you, and it's a big, like a bicycle wheel, or I think I call it a pizza in the book, but that's sort of what it looks like. But it's based on the ideas of the British philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham, and the idea of the Panopticon. So, yeah, like a big, big pizza with a giant tower in the centre. And from that tower, the guards are meant to see every part of the prison. And it was part of social reform, actually, it was meant to be… allow for a much lighter touch, for guards and so on, because they could see everything anyway.

So, it was really part of that, sort of, utilitarian movement and so on. In theory. In practice it was just a dirty old jail. And the guardhouse which I describe in the book as, sort of resembling, some of those structures in Lord of the Rings, because that's what it's like. And will never forget the door – this giant wooden door – so big that it was hardly ever opened. And there was a small door to allow human beings to come in and out. But yeah, no, horrific place. Over 100 years old, I think it was built in about the 1890s. So it was every vision of a dungeon, like with concrete, and damp, and smelly, and rusty old iron bars, the whole thing. And the cells were all open to the elements. And so you would get obviously the awful weather would come in, but the insects, and the rats and all the rest of it. So / yeah, no, it was pretty horrible.

Melissa Crouch: / So quite a contrast to The Box where you were alone /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / it was a closed room, /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / it was often hot, and the generator wouldn't work, /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / and it was stuffy. Whereas now you get put in this, this open air environment, but also you have people /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / around to tell us about the people /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / you met.

Sean Turnell: So the people were fantastic. So particularly, on that day when I was moved into the prison, and of course I'm feeling really bad anyway because, I'd still maintained a hope that I might have been deported. And this told me that I wasn't, that there was going to be some sort of legal process. So it was an awful, awful day, but I was relieved at the end of that day. So, I get escorted into the prison, taken to this area where my cell was, and this young man just came up to me. And bizarrely enough, but this is very Myanmar, in the prison wearing a t-shirt with Aung San Suu Kyi face on it. And just came out to me and said, Sean you’re safe now, you’re with us. And this young man, Pai Yai Tu, his name is, a wonderful person, and I'm pleased to say he's out, and he's free, and he's safe. But yeah. So, then all of them, they just gathered around me, all these young people who’d been protesting against the coup, and they were all full of spirit, totally unbowed, which they remained all the way through, actually, in every single prisoner cohort I was with, remained like that. I didn't see anyone crack, anyone, you know, kowtow to the regime or anything, actually. It was most yeah, incredible… and done with just great spirit. Wasn't even done with anger. It was, yeah, very interesting. But yeah Pai Yai Tu, and the whole team just sort of looked after me from then on.

Melissa Crouch: Yeah.

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: Tell us about some of the other characters. So you speak, in particular, about Muslim gentleman Khin Maung Shwe, or Ya Kut, /

Sean Turnell: Yeah, so…

Melissa Crouch: / who befriended you.

Sean Turnell: Yeah. That’s far away the most, like, individually tragic thing for me. So Khin Maung Shwe, a wonderful man. Always went by the name of Ya Kut. One of those people who you will remember from your school days, who stood up against the bullies. Often, you know, against their own interests and Ya Kut was just like that. And he particularly looked after me, and would really get stuck into people who perhaps were ill treating me, and cook for me, and done all sorts of things, just, incredibly capable man. But because of that, the guards didn't like him at all. And also he looked the part, so, he had the full beard and all the rest of it. And the guys were frightened of him, frankly. And yeah, so he was wonderful. But six months in, I get taken from Insein, up to Naypyidaw, Naypyidaw jail, and I left all those people behind. Spent a year in Naypyidaw, then get convicted, taken to another prison, called Yamathin, very, very briefly, then taken back to Insein in Yangon. And the first thing I did when I got back and got to Yangon, when I got to Insein, was to say, where's Ya Kut? And I'll never forget the answer, because, at first somebody, another good friend said to me that, oh, he's gone. And I said, oh, that's fantastic, he's gone out! You know, because there were sort of odd releases, all the time. And he said, no, no, no, no, no, Sean, no. I mean, he's dead. And I was just, you know, so taken aback and it took me ages to work out what happened, actually, because the guards, even even the good ones, were very embarrassed by this, and ashamed by it, but eventually got the story that he'd been beaten to death, beaten and kicked to death. That they'd been an invented fight, which characteristically, he'd entered to try and stop. But the two protagonists, who were in the pay, I guess, of the guards, turned on him, and then the guards did as well. So yeah. So there's a photograph of him in the book, but certainly, yeah, his memory is very precious.

Melissa Crouch: Tell us about some of the sort of variety within the community in Insein, in particular. So you talk about many of the political prisoners who were there, but you also talk about some people convicted on drug trafficking, a whole, sort of, assortment of people. Tell us a bit about that.

Sean Turnell: Yeah, again, right? So I'm someone who never got a parking ticket, an8 academic all my life, and I'm suddenly with drug traffickers, fraudsters, kidnappers, murderers, everything. And this is going to sound very odd, but most of them were very, very nice people. But the young Taiwanese drug traffickers were particularly good, and particularly innocent, it seemed to me. They, I don't know, I mean, I'm sure… well, I'm not sure, but I think they probably did the deed they were in prison for. But they were very innocent in their ways of the world and all that. I got on really well with them. Yeah, a few other people, some I'm sure, as most people know, Myanmar's legal system — if one can even call it that — is incredibly corrupt. And so there were a few people who were, yeah, I think, really were innocent, but on criminal convictions. But yeah, all sorts of bizarre characters. A bunch of Nigerians who were there because they'd, again allegedly, fiddled with ATMs in Yangon. But their situation was sort of tragic, because they'd been given relatively quick sentences. So they were meant to be released, but no one would have them. The government in Nigeria wouldn't help them, or get them back, so they were stuck in Insein. But yeah, really interesting characters though, very, very funny.

Melissa Crouch: So this is during COVID 19 /

Sean Turnell: Mm hmm!

Melissa Crouch: / You know, I think being under arrest arbitrarily would be sufficiently scary in normal times. But we know that prisons around the world were struggling to contain outbreaks of COVID within the prison. How was your health? What exactly did health care entail in the prisons?

Sean Turnell: Well, there basically was no health care. Actually, I got into a conversation with the prison doctor at one point, where he told me that the budget for one prisoner per year, the health budget, was, I think, about $0.22. So, yeah, so, and that had to, you know, cover everything. So, yeah, so just awful. And on COVID, and in the book I spend probably too much time talking about the unsanitary conditions, and the sharing of food out of buckets, and all that. But it was a system designed to spread disease, basically. So you're getting sick all the time. So I… but I did get the jab, the vaccine. It was the Sinopharm and the Sinovac jab. I got both of them twice, and I got COVID five times, which, sort of says something, perhaps, about those jabs. But yeah, no, there was no way to control something like COVID, at all. But the regime went to very great lengths to show that they were protecting me. So my inoculation was actually televised. I'm not sure, live, but it certainly made the evening news on MRTV, which…

Melissa Crouch: And they also seem to take your pulse quite often, I understand? What was the reason for that?

Sean Turnell: All the time. So it didn't worry them ill treating me, because, and I think they wanted to do that, to send a message. But they were pretty desperate that I didn't die on them. So they were constantly checking my pulse. And so I've had my pulse taken more times there than anywhere. I can still feel it, the way that, you know, that thing puffs on your arm, to get the measurement. But yeah, every few days it seemed.

Melissa Crouch: So while you're in prison, your wife, Ha /

Sean Turnell: Mmm hmm.

Melissa Crouch: / is here in Australia. /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / Doing all sorts of things /

Sean Turnell: Yes.

Melissa Crouch: / on your behalf. Can you tell us a bit about her extraordinary efforts /

Sean Turnell: Yeah, and…

Melissa Crouch: / government and elsewhere, and how some of that also reached you?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, so, I mean, it was just extraordinary and Ha is here tonight, and also Melissa, yourself and other people I know in this audience, were all part of the apparatus that Ha was the creator and head of. But yeah, no, just incredible mobilisation. It's um, yeah. And the details of which actually I'm still finding out, still every day I find out something new. But yeah, eventually the embassy was able to establish contact with me, in the whole 650 days. I never saw the, I never had any physical contact with the embassy at all, but they were able to get things to me. Which then through Ha, a whole bunch of things down and coming my way. Food, and the famous story of Ha cooking, these alcohol laden fruitcakes, and I really do mean alcohol laden, which she would bake, seal in a airtight, vacuum sealed bag, and from our apartment here in Sydney, would make their way down to Canberra, to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, where they would then go strictly against the regulations, in the diplomatic pouch, and then make their way over to Yangon. And when I was in Naypyidaw, an extra journey up to Naypyidaw, and so on as well. That was wonderful. I will never forget the smell of the cake as I opened up the vacuum seal, and get this whoomph! And yeah, so there was that. And then the books as well. So again, you know, books are everything, in my life, always have been. And now they returned the favour and saved my life. So Ha was able to get books to me. Friends everywhere, and again, very much in this audience, were able to get books to me. And it was the one thing that the prisoners were allowed. I was always vulnerable, was that they would take them away again. I hasten to add. And so, yeah, you can never feel assured, but I was able to build up a huge inventory of books. I was only ever allowed to have ten in my room, at any… in the cell, at any one time. But I think there was about 120 odd books that came my way.

Melissa Crouch: Any favourites in particular, to just indulge us?

Sean Turnell: Yeah, I mean, Lord of the Rings is there, and you can see its imprint all the way through my book. My favourite of all, I think, was a book by someone who I'm sure people remember called Clive James. Wrote a book called Cultural Amnesia, that was really good. And it was about, in a sense, the defence of liberal values, and with a particular focus of Vienna before World War Two, and the destruction of that community. And it’s a really… it's a very deep book, and it's sort of, Clive James, is sort of known a bit as being a comedian. You know, he wrote those unreliable memoirs, and the TV shows and all that. But behind that was a very deep thinker. Yeah, and the book was just fantastic. But so many others, in fact, we could easily, I could easily talk the whole time / on that

Melissa Crouch: / just have another session on that.

Sean Turnell: But yeah, but both those two stand out. But my sister sent me Enid Blyton's Famous Five, which added a certain spice to it as well.

Melissa Crouch: So in addition to those books, you mentioned that you have a preexisting fascination with prisoner of war stories. /

Sean Turnell: Oh yes.

Melissa Crouch: / I'm not making this up. /

Sean Turnell: No no.

Melissa Crouch: How did this inform your experience? And in particular, what was the kind of dilemma /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / that you found yourself in as a prisoner, in terms of, how you exercise your agency and respond in that situation?

Sean Turnell: So I, I misspent my youth reading books, graduated from Enid Blyton, and then straight into that cohort of books written about Britain in World War Two, basically. So books about, you know, flying aces and all that. But I became particularly obsessed about Colditz, The Great Escape, and all those prisoner of war stories, where the absolute duty of a prisoner of war was to escape. And I remember thinking at one point, in the middle of it all just, oh, wait a minute, here I am in a pri… shouldn't I be trying to escape? But then, thankfully, I suppose, I quickly dismissed the idea because, you know, appearing as I do, what would I have done, if I'd gotten out the other side of the gate? I think they would have picked me up fairly easily. But yeah. But it was on my mind, I remember thinking, looking around at the walls and and the gates and all the rest of it, and thinking about how you build a tunnel or, you know, build a glider or whatever. But yeah.

Melissa Crouch: But, it didn't happen. But you did have some acts of resistance, or ways in which you tried to, kind of, retain control /

Sean Turnell: Mmm hmm.

Melissa Crouch: / because that's, sort of, a big theme in your book. This sense of, you know, a real loss of control, and ways of trying to, you know, assert yourself. Tell us about some of those.

Sean Turnell: Yeah, some of those I'm not especially proud of, actually, because they're more like the actions of a toddler, just having a tantrum, to be honest. So a few times I would just lose it completely, which was something my Burmese colleagues never did. They were calm, always. I never, again, never saw anyone, you know, yeah lose it, in the way that I would, every so often. So the one thing you were never, ever allowed to do was to touch the bars of your cell, much less shake them. But I remember one particular night, I just had enough and I just got up and I started shaking the bars and, you know, and the guards, yeah, sort of, let me go, let me go at it. And then some of my Burmese friends the next morning said, Sean, are you okay? And I said, Well, look, it's fine, yep, it’s fine guys. This is an Australian way of letting it out, because they would meditate and do all those things. And, you know, I just couldn't do that. So yeah, so things like that. Well, some other things, I remember when I was made to wear the longyi, which is sort of like a sarong type thing. After being convicted, you have to wear the prison outfit, and it was a blue sort of longyi. But tying a longyi is a real art, which I never mastered. So I would just sort of tie in any old way just to send a signal back I didn't care. Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: And you also grew a beard.

Sean Turnell: Oh, and I did grow a beard! That's true. That's very true. Yes, I remember one mor… and it was always hard to, like, again, some of the stuff that Ha sent me included razors and all that, but every so often they would stop them coming in, it was just a hassle. And I thought, what am I shaving for? In fact, why am I dressing up to go to the court every week? And I thought oh bugger this, No. So I just, yeah, let it go and just, you know, even dress however I liked.

Melissa Crouch: Small acts of resistance.

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: So from Insein, you were moved to Naypyidaw prison, and I think, you know, even for myself, reading about that was quite new.

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: Tell us about how that was, kind of, different from Insein and some of your experiences there.

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So it was a new prison, as indeed, of course, as we know the city is. So this bizarre capital, built in the middle of the country. All the buildings are new and so on, but very badly built. So even though this prison would have been no more than probably about seven or eight years old, it was already falling apart, and crappy. And it was just, in a clearing, in the middle of a sort of swampy, awful, sort of, mosquito infested place. And just so hot. Because, again, for people who have been to Naypyidaw, will know, it's just, yeah, so hot there, all the time, just unrelenting heat. Yeah. So it was an awful place. And so I guess Yangon had the you know, the upside of lots of trees, even in Insein prison. So there was a bit of shade and all that. But this was just a sun blasted plain, on which this prison had been built. And yeah, just an awful place. And the people who ran it were awful as well. And, and I think basically because of the proximity of the generals. So this is right in the lair of the regime. So, they had to be careful not to treat this very well, basically.

Melissa Crouch: Mmm mmm. And you talk a bit about the monsoon. /

Sean Turnell: Mmmm!

Melissa Crouch: / and how you survived that with your possessions in the cell.

Sean Turnell: Yeah, so, again, in the awful building standards of this place, in the monsoon, which lasts for months, right? And the rain is just so heavy and it would come through the back window. So the cell was open with an iron bar door at one end, but there was a window behind you, about, very high up, and that just became a funnel for the water to come pouring through like a waterfall. And the floor of the cell would just fill with water. So if you had books or anything, you could, you didn't want to get wet, you just had to hold them. And so, yeah, if the monsoon was at night and there was a blackout, and you'd be just standing up all night holding the books, holding the stuff you couldn't bear to get wet, and just standing there all night. And that that was… in fact, some of the meltdowns happened at those occasions, because, again, there's no light, I couldn't read anything, and I’m just standing there just thinking, oh god, this is, please make this end. Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: But during the daytime you were able to interact with other prisoners there, and you talk a bit about the barbed wire university, /

Sean Turnell: Yeah!

Melissa Crouch: / Tell us about that, /

Sean Turnell: So /

Melissa Crouch: / in Naypyidaw.

Sean Turnell: So, they concentrated the senior political prisoners together. So I was there with the ministers, and the people who I'd worked with. Incredibly clever people, but much more than just simply clever, great economists and all that, but great thinkers, readers, wonderful experienced people. And we would need to talk… so we got released for two, two hour sessions, morning and afternoon, and we would just come together and just talk about all sorts of things. I don't want to suggest it was too highfalutin, there was plenty, sort of, silly nonsense talk as well. But we, yeah, we would talk about, like, economics and the reform program, where we'd gone wrong. And one of them in particular, this wonderful man who I won't, I’d better not mention his name, but people know who I'm talking about. Just so enthusiastic about reform, he would start drawing up new plans. He'd smuggled a pen in and we were drawing new economic plans. And ok, sure, now when we get out of here, we're going to do this, and then that, and then we'll do this, and then we'll do that. And then after a while, you sort of forgot where we were, and just thought, okay, but yeah, all sorts of topics. And we ‘d just sit in this drainage ditch, where we conducted our seminars of the, yeah, what we called the barbed wire university.

Melissa Crouch: Mmm mmm. So you mentioned a pen there, and I think /

Sean Turnell: Yes!

Melissa Crouch: / in the book you talk about the pen as being /

Sean Turnell: Yes.

Melissa Crouch: / contraband and it was actually your /

Sean Turnell: Totally.

Melissa Crouch: / precious. Is that /

Sean Turnell: Yes

Melissa Crouch: / Right?

Sean Turnell: And normally /

Melissa Crouch: As a Lord of the Rings fans?

Sean Turnell: / I'm a pen aficionado, right? And I hate scratchy biros, and you know, I won't have one near me. But there the only pen I had was this awful, broken, little old Bic pen, the end was chewed off and all the rest of it. But it was so precious! Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: Small things. Did you want to tell us any more about some of your coping mechanisms? So one of the things I found interesting is that you said, you know, yes, many of the other prisoners meditated, wasn't for you. What were some of the other things, ways that you used your mind, and exercise as well?

Sean Turnell: Part of it was writing the book, actually. So about a third of the book was written, purely memorised. And again, I mentioned that my memory became this incredible thing, for the period I was in the prison. And so I would memorise the book, even down to the detail of re-remembering it every day, and I'd modify it, I would edit it, even just moving commas, moving particular words and so on. And I would remember the next day exactly where I’d got up to. And so then that became a real thing. And so, yeah, in fact part two of the book is almost exactly as remembered. And then, to stray from memory, when I got back to Australia, I didn't even need to think about it. It was just transcribing. I didn't have to write it, it was just “tch tch tch tch”. Yeah, so that was part of it. And then, yeah, like reading books over and over and over again and um…

Melissa Crouch: But you talk about music, a little bit /

Sean Turnell: Yes!

Melissa Crouch: / and with the legal trials, /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / which were something /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / of an ordeal. /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / You talk about the way in which humming tunes /

Sean Turnell: Yes! Ha ha!

Melissa Crouch: / to yourself was a form of centering, if you like.

Sean Turnell: Yes! So, you were forbidden to whistle. And for people who know me, I whistle all the time! And I don’t even know I'm doing it. But it was forbidden to whistle, or sing, or anything like that. But music means a lot to me, even though I'm completely ignorant of it. And I know… I can't play anything or know nothing about it. But yes, I would sing songs to myself all the time, but the particular one that I was always singing when the… and again, this this is going to take me back to the issue I mentioned earlier, the song that I would always start humming at the deepest, darkest moments was the theme song to the 1969 movie The Battle of Britain. And it had such a stirring theme, and I would, sort of, hum that to myself and lift my spirits up. And yeah.

Melissa Crouch: Mmmm. Tell us a bit about those legal trials. What was it like?

Sean Turnell: So, totally absurd and… beginning with the location! So the location was a house that they, sort of, made up as a courthouse. But, you know, even the central dyas where they'd place the — can’t remember what they call it — the big book of evidence, or whatever, all the documents were put together, it was mounted on a stand. But if you looked — and it was, sort of, covered over with a tablecloth — but if you looked under the tablecloth, it was chairs just stacked on each other, and, just, it was just so ridiculous. And there was a coat of arms that would fall off the wall. And, you know, I mean, it's just absurd. So, but it was a wonderful metaphor for the proceedings. Yeah. But the proceedings themselves were totally ridiculous. I had people turning up who said they knew me and I'd made all these confessions to them, of my spying activities. There were documents presented which were just absurd. I mean, one of the more obvious ones, which I didn't notice, one of my colleagues pointed out. They would put what they thought were incriminating documents, they’d project them up on the wall, and one of them was a document, again, a really innocuous economic reform document, with the word top secret across it. But what they hadn't done, was to, or what they had done, was to leave the date of last modification of the document on the bottom. And so you see whether they'd actually just doctored it, just cut and pasted top secret onto this document. So, yeah, just completely absurd. And then finally ended with the, when we were convicted and we were asked to stand up and all that. And I was made to have 3 minutes after a trial, that had gone a full year, I had 3 minutes to, to basically sum up my defence, but I only got 90 seconds in the end. And then the judge, sort of, read out the verdict in a rapid, staccato, sort of way that was almost like, as if he was mocking the process. And to be frank, I think that is what he was doing. And then disappeared out of the room. So, yeah, it was just, you know, the whole thing was just ridiculous. From one end to the other.

Melissa Crouch: So you also dabbled in poetry, a little bit.

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: Is that right?

Sean Turnell: I hesitate to call it poetry, Melissa!

Melissa Crouch: But I thought we might read a little bit from it /

Sean Turnell: Okay.

Melissa Crouch: / Just to, get into your mind a little bit more. In particular to emphasise the way in which Ha was so central to your, kind of, reasons for keeping going. So in the book, Sean includes a poem, which I think was on the second anniversary of your imprisonment, is that right?

Sean Turnell: The first anniversary!

Melissa Crouch: First anniversary. /

Sean Turnell: I’m looking at Ha to get confirmation! /

Melissa Crouch: / Oooh, well it starts with the second, so we will go with the second. Maybe it was the first /

Sean Turnell: It, it…

Melissa Crouch: / but it also indulges /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / Your love for economics, /

Sean Turnell: Yes.

Melissa Crouch: / which Ha shares, as an economics professor. Would you like to read it? Actually?

Sean Turnell: Oh, no, please, please!

Melissa Crouch: Okay. All right. The poem is called Bonds and Bonds. Sean Turnelll for Ha Vu. Second anniversary finds us apart. A test, a challenge, for sure, my stout heart. The debt that I owe you, my Hanoi true blue, hopefully, surely is soon to be due. A bond of six zeroes, nine zeros, 12 zeros, more. Certainly beyond that, which Jay Powell can keep score. Infinity, now that's the face value I want. A figure so big, best writ in small font. Love you forever, my darling Ha Vu. The gilt, the sovereign, I know that is you.

Sean Turnell: Ha ha!

Melissa Crouch: And what did you give a mark for yourself, for that poem?

Sean Turnell: Well, yes, I'm begging forgiveness and maybe a C for effort. But I /

Melissa Crouch: I reckon it’s pretty good.

Sean Turnell: / I had some serious conversations with political prisoners about the importance of poetry, and they were very impressed when I said that I'd written poetry. And then I said, no, no, no, you haven't seen yet. Ha!

Melissa Crouch: So I thought tonight it would be good to include something extra that is not in the book. So your publisher wanted you initially to write this as a love story. It's obviously a story about many things, and there is certainly the love element to it. But tell us in particular, what was the special way that you and Ha stayed in touch? So particularly in that first period, you had very few calls, and then maybe later on it was once a week? As I understand it. So not a lot of contact, only 20 minutes. And sometimes the connection wasn't good, as you say. But tell us, how did you stay in touch during the 650 days?

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So this is really interesting and it's not in the book. And which again, goes to the issue, you know, I’ve mentioned about my memory being this super instrument in the prison. But since getting out, it’s kind of fallen apart! But one of the things Ha and I did very, very early, from day one, more or less, was we — and then we were able to formalise this when we got into contact — was essentially to decide upon a very precise time, every single morning, that we would think of each other, really intensely, like in those ways where you just concentrate on the other person. And from memory it was about 4:30 a.m, on Yangon time, which is when we were roused to wake up. And for Ha, it would have been about 9 a.m, I think, in Sydney, yeah, it would have been 9 a.m. And we would think, we agreed that we would be thinking of each other at those moments. And it was incredible actually, because, and particularly in the early times when, by that time I still hadn't had books and, you know, still finding my feet and all that. But you really felt in contact. It was very extraordinary. I don't mean this in any spooky, supernatural sort of way, but it was yeah, it felt like we were in touch.

Melissa Crouch: Obviously, Ha also played an enormous role with DFAT, in connecting with people around the world, but as you say, through books and other things, that was really extraordinary, and that I want to acknowledge tonight. And I wonder if we could maybe just acknowledge that formally by giving Ha a round of applause. *audience applause*

Before we turn to questions, Sean, is there anything else that you wanted to add to what we've said tonight? There is plenty more in the book, a lot more stories, a lot more acts of kindness, that you highlight by many Burmese people that you met in the prisons. The translators, many people along the way who helped you out. Is there anyone else you wanted to highlight in particular?

Sean Turnell: So probably the only thing, just like the broader feeling, because in a few of the podcasts I've done, people said to me, you know, do you feel bitter or do you, you know, do you view humanity in a different way? And my answer to that is probably the opposite of one expected, actually, it’s increased. Because not only the extraordinary acts of kindness, compassion and courage and someone that I encountered in the prison. But since coming back to Australia, the average person that we meet in the streets. Ha and I, we go on this very long walk every morning, and even to the present day, it's lessened a little bit now. But, for a while there, multiple times a day, we'd have people coming up to us, and very emotionally affected by it. So in fact, for the most part people would tear up as they were just saying what they felt about it, and all that. And that has made me think a bit about what this meant and so on, and what people were feeling. And to some extent it's a mystery, but it's very gratifying. And yeah, just the support of everyone, the support of everyone here coming to an event like this, it's so affirming. So there's a yeah, there's a goodness that, in a sense, I think that we've been able to discover.

Melissa Crouch: Yeah, I know there's certainly probably a number of people in the audience tonight who signed petitions /

Sean Turnell: Right.

Melissa Crouch: / who might have written to their local MPs /

Sean Turnell: Indeed. Absolutely.

Melissa Crouch: / to show their support. But we know, of course, that your situation is perhaps emblematic of the broader situation in Myanmar /

Sean Turnell: Mmmm. Absolutely, yep.

Melissa Crouch: / which continues, and we acknowledge and recognize that there are many people still in prison. /

Sean Turnell: Yep.

Melissa Crouch: / And obviously, people of Burma at large, /

Sean Turnell: Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: / who continue to live through military rule.

Sean Turnell: Yeah, And that, I suppose, is something just to highlight as well. So having said that, you know, it restored faith in humanity, and so on. For the people of Myanmar, are just suffering incredibly. And one of the strong motivations for the book, apart from paying tribute to these friends of mine, and people here for helping me, and all that. Is to somehow elevate the story there, because it just slipped way down the list of international attention. And yet the atrocities there, the killings there, you know, surmount most of the other events going on in the world. And yeah, it's really quite tragic.

Melissa Crouch: So the first one we have here is, has your time in prison changed any of your habits, body and mind? And do you feel your brain was changed by the experience?

Sean Turnell: I've stopped pacing. I don't do that anymore. Still do the step counts, but this does it for me now. Other than that? Yeah. No, I don't think so. I've had a bit of a problem finishing a book. So in the prison I would finish a book every day and a half, roughly. And you just keep on, then read them again and again and again. Took me about six months before I got to the end of a single book, I think. But no, other than that, I don't think it's changed a lot. And the unfortunate aspect of that, which I've hinted at already, is that, certainly the memory is no longer there. But yeah, no, I think fundamentally things are the same. And certainly, my inner core beliefs about the importance of economic freedom, there, about the importance of the rule of law. And, you know, in a broadly liberal democratic society, more entrenched than ever, obviously.

Melissa Crouch: And those beliefs and that foundation really come through, in the book, I think.

Sean Turnell: Mmm. Yeah.

Melissa Crouch: I have a question here about children of military officers. So many military children have Western education, and have been exposed to the outside world. Do you think the current system can change as new generations take over?

Sean Turnell: It's really interesting, that. One of the things that gives me some hope about Myanmar, is firstly, recent events where this terrible regime has suffered some big reversals on the battlefield, and we're now beginning to glimpse the possibility that these guys are not going to last much longer. So, that’s a positive thing. The other positive thing though, is the new generation of people in Myanmar who are just extraordinary. Obviously, the ones I encountered were not so much the kids of the military, but others, much braver ones, if I may put it that way. But I think more broadly, the young people in Myanmar are incredibly impressive, much more open to the world. So some of the terrible things that took place even during the civilian government, the atrocities against Rohingya and so on, totally different attitudes over race, over ethnicity, over gender, all that sort of stuff. I mention in the book, just, actually the incredible, kind and compassionate way that LGBT people were treated in the prison. Which somewhat surprised me at the time. But probably shouldn't, in retrospect, because again, amongst these younger cohort, yeah, some of those issues, a little bit like in Australia amongst the younger people, these are not issues, these are… yeah. Yeah. So, but on the military kids it's all a bit, it's a bit odd. I think it goes person to person. There's… some of them are just horrible, frankly, and spend their time putting pictures on Facebook of racing around in Lamborghinis and all the rest of it. But, some of them understand what's going on.

Melissa Crouch: Some questions here seeking your economic advice. So, if you had your time again, how would you manage the bad loans issue with major banks in Myanmar?

Sean Turnell: Ooh! /

Melissa Crouch: Just a…

Sean Turnell: / Now, this is my bribe patch. Ha! Well, so, you know, we were always going after the bank… I should explain that Myanmar's banks, for the most part, are criminal entities, for a start. Secondly, they're completely insolvent, and not just a little bit insolvent. The non-performing loan, or unpaid loan ratio of Myanmar's banks is around average about 60% of the loans out. By comparison, in the GFC it was about 6% right? So this is ten times. So yeah, the banks are completely insolvent, all that. But they're very sensitive and they were part of that cohort that I think were, you know, encouraging the coup and so on. There were some good players amongst them, but unfortunately they're outnumbered by the bad ones. So I think what would need to happen, would be to do that very quickly, a little bit like a Band-Aid, just take it off. I think the state needs to come in, guarantee deposits after an investigation of some of the hairier ones, if you like. And then the whole system needs to change, actually, but… and it needs to be done quite quickly.

Melissa Crouch: So I have a bit of a dilemma here. So the question is, would you choose to continue advising Myanmar's economy under military rule, if it could help prevent the current economic downturn? I think that's slightly generous. It's not a downturn. It's a complete collapse /

Sean Turnell: Yeah. Indeed.

Melissa Crouch: / of the economic system.

Sean Turnell: And it's the military rule that is the problem. So the answer is very easy. No, I wouldn't, because Myanmar's economic problems are not technical. It's not about budget deficits. It's not about anything narrowly in the realm of economics. This is politics, in its raw sense. And it's inconceivable that this, particularly this military regime, would ever be in a position of reforming the economy, has no credibility. It's not even in their incentives to do so. So, yeah, I wouldn't, I think.

Melissa Crouch: And just another easy one for you. So what can Myanmar do? And I think here the question is referring to pro-Democratic supporters, and those opposing military rule. To attract international interest, and to support the overthrow of the military? Because it feels as though Myanmar is currently forgotten, given other geopolitical and diplomatic issues.

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So I think that the major thing on this front is not only for the world to pay attention, but also for the capitals around the world to recognize that this military is not there for the long term. I think there's an assumption sometimes, particularly amongst diplomats who like to see themselves as realists, that somehow the military we need to deal with them. Come on, we need to deal with them. But that's actually not true. If you look at it, this is a regime that is not there for the long term, almost regardless of what's happening at the moment on the battlefield. Their own internal divisions, etc. Their instability. This is not a regime, if you are an investor, for instance, that you could, in any way, trust to put money on the table. So, it's realistically not a partner. And I'd like to see governments recognize that, and then make the obvious calculation, that we need to support someone else.

Melissa Crouch: So I'd like to just check, are there any questions in the audience? So we have two microphones, one on either side and you can feel free. Yes. The gentleman here, if you'd like to come to microphone one? Is there anyone else on this side who'd like to ask a question? Otherwise, I'll come back to one or two questions here. Please go ahead, sir.

Audience Member One: Thanks. Sean, can you tell us a bit more about the present? We hear reports about the regime losing a lot of people, and a lot of them have surrendered. I heard that, through CNA, that the Indian Army is bringing some of the soldiers back. And also a lot of them have surrendered, the people in, in Chin State or Karen, and all that. How tremendous is that? Are they able to overthrow the regime?

Sean Turnell: So I think we can imagine the possibility of that. I mean, and I should say, you know, I have an economic hand, not a not a military one. So I'm a consumer of the information like you are. But, you know, it certainly seems that way. And in my own area, I suppose, I can see the evidence that supports it. Because it's not just defeats on the battlefield, it's the way in which all economic policy at the moment is fixated with one end, and that's to get as much resources as possible for the military. In a practical way, it’s often about foreign currency, because they need foreign currency for the munitions, for the weapons and all the rest of it. The only thing they've really got is air power now. So they need cash for that. They need hard currency, and everything is bent to that. There's almost no other economic policy. And the interesting thing, which just backs up the idea that they're on the back foot, is that they're not even pretending anymore. There's no long term economic reports coming out. There's no celebrating of educational investment or anything like that. So I think, yeah, the economic evidence backs up what we're seeing in the military sphere as well.

Melissa Crouch: I think we have another question. Please go ahead.

Audience Member Two: So I would like to say thank you, Sean, for your service, because if it weren't for that, many of us Burmese students wouldn't be here in this room as well. So thank you, first. And my question is, in your opinion right now, what do you think is the main ingredient that we need for the revolution to prevail? And if the revolution were to prevail somehow, what are the things… what are the major issues that the country would have to struggle with afterwards post the situation right now?

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So with the first one, I think it comes down to international support. That's what's needed now. And again, militarily, Myanmar's democratic opposition gets nothing. Zero, basically. And with just a modicum of support, particularly against I mentioned, air power, which is the one thing that the regime has. One can easily imagine an overturning of the current dynamic. So international support, above all. The people of Myanmar can then take care of it. It's not… it doesn't require military intervention or things like that, but they can do the job. Obviously the critical thing is then on the Myanmar side, and a certain degree of unity, it doesn't have to be you know, everyone doesn't have to agree with each other. But a sort of unity of purpose about throwing the regime off, in a very clever then crafting of what might follow that politically. But that's where I also feel very confident because, again, you know, to highlight the younger people, particularly in the opposition movement, the national unity government, and so on, they’re incredibly impressive. And very, very thoughtful. It's not even, I think, just being impressive. If you look at things like rules of engagement, the standard operating procedures they're using, and all that. This is really high quality stuff. Likewise, you know, throw the military out and I'm incredibly optimistic about the place. And that things could happen quite quickly. Because one of the upsides to the terrible downside is that the regime has so destroyed things, here talking economically, and in such obvious ways, that fixing it could actually be quite quick. Like the rebound in GDP, for instance, if a decent government was to come in, it seems to me would be very, very rapid. Likewise, there's no technical or intellectual barriers. It's all been done. Melissa asked me about the plans for the second term, it’s all there, you know, there's no, as I say, no intellectual barriers. There's certainly no human barriers in terms of the skills of the people. So, yeah, get the military out of the way. And I'm quite confident about what could follow.

Audience Member Two: And by international support, could you specify, like, what kind exactly, and also, like, what incentives or how to, like, make those really… how to really prompt the international community to really do those actions? You know?

Sean Turnell: So I suppose with what could prompt them, I mean, Myanmar is strategically located, right? So it's wedged between China and India. It's a key player. China's very, very anxious to get that deep sea port at Zhao Pu, which gives them an opening to the Indian Ocean. Likewise, Myanmar is incredibly important for allowing China to avoid the Malacca Straits, when it comes to oil imports and so on. So it's an incredibly important strategic play. So it seems to me that for the world's powers, Myanmar is a country that they really can't afford to lose. So that should be motivation enough. Let alone of course, we would also like to think that we might intervene, or support, rather, the people fighting for human rights and things like that. But yeah, Myanmar's incredibly strategic place, and I don't know myself, I think in terms of like the actual material that would need to be supplied. But in some ways, in talking about, you know, aircraft and things like that, it sort of would follow that. I would think.

Melissa Crouch: So, I think that looks like all the questions from the floor. I might just take one more from here, which is, there are a few questions simply asking about you, your wellbeing, given that the trauma that you've been through, and whether you've completely recovered? Now, I understand recovery did involve eating a lot of ice cream, because you had to put on weight again. But tell us, how have you recovered from your ordeal?

Sean Turnell: Yeah. So that’s been a change, I think. I don't think I have an evening without ice cream. Ha ha, looking for confirmation! No, recovered pretty well. I have issues to do with sleep, but, you know, so don't we all? And I have a recurring dream of being in the prison, and being given a sheet of paper that allows me to leave. And I go up to the gate and present it to the guard, and something's missing. Always. There's a stamp that's missing on page five, or a missing signature, or something like that that holds the process up. So I usually sort of awake yelling that particular one. But I did think recurring dreams were just Hollywood, but it seems that they’re real. No, other than that, pretty good. Usual ailments of a now 59 year old guy. Teeth! Teeth are the things, how can I forget that? I broke my teeth a couple of times, in the prison, on little stones or little bits of iron, I think they were, that were in this awful rice that they used to give us. And so I'm still in the process of getting my teeth fixed, and I’m a terrible coward when it comes to the dentist. So that's a major area of recovery, I think, is in the dental realm.

Melissa Crouch: Mmm. And maybe we should end… So I haven't come to the day you were released.

Sean Turnell: Mmm.

Melissa Crouch: It was a surprise, right? Tell us about that day.

Sean Turnell: It was a total shock, because… so, Sixteen November 2021 was my wedding anniversary. And it was also, just by coincidence, one of the days that I could talk to her on the phone. So I'm talking to her on the phone. And we were pretty depressed because by that time I'd been convicted two months earlier, I was down in the Insein prison. I was amongst the prisoners on death row, it was a horrible place. And we'd given up hope, because the moment for release would have been the last moment of release, would have been the day I was convicted, because Myanmar has a history then of deporting foreigners. And so the fact I was then taken to another prison, and then taken to Insein as well, didn't look good. And so we were reconciled in our conversation that day, that I would miss another Christmas, and that it would be March 2023 at the earliest, before I would go. So then the next day, and I'm doing the exercise, I'm doing my steps, and the guard suddenly appears and says, Sean, good news, you're going home. And I didn't know what to do. I was frozen, just didn’t know, and my only reaction was to say, please, please tell me that you're not kidding. And he wasn't. But I had to pack really, really quickly. And I ended up walking out of there with almost nothing. But it was very, very surreal. A mixture of extreme elation, but extreme anxiety as well, because there's also a bit of a tradition in Myanmar amongst this regime of releasing people and then re-arresting them outside, for another charge. And yeah, so I was fixated on that. And then… but then we were put into a bus and driven towards Yangon Airport. And so as the bus is going along, and there's a few other political prisoners with me, including some foreign, prominent foreign ones. And the hope is rising as we're coming towards the airport, and looking out and thinking, oh! But I do remember, actually one more anxiety. I was never allowed to wear shoes, so I had no shoes. So all I had was some, what we call thongs. And I thought, are they going to let me on the plane wearing thongs? And they did!

Melissa Crouch: Good. Well, we've come to the end of this evening. There are books, I understand, for sale, outside. I want to thank The Centre for Ideas here at UNSW for hosting us tonight, and hope you'll stay around for a bit of a chat.

We've heard from Sean the economist, the amateur history buff, the friend of Myanmar, the optimist — I think you'll agree with me — and the storyteller. So thank you, Sean. And please join me in thanking him.

Sean Turnell: Thank you. Thank you everyone. Thank you.

Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. For more information, visit centreforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

-

1/4

Sean Turnell

-

2/4

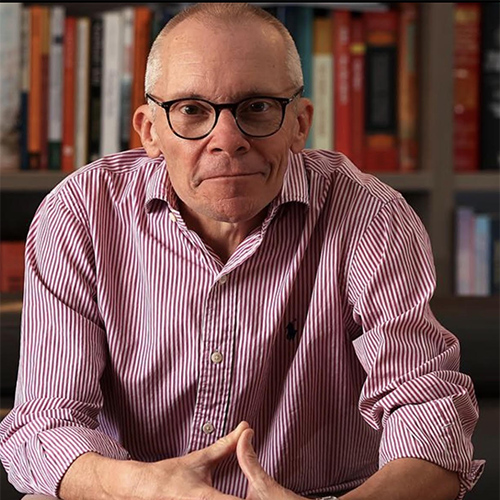

Melissa Crouch

-

3/4

Sean Turnell and Melissa Crouch

-

4/4

Audience

Sean Turnell

Sean Turnell has been a senior economic analyst at the Reserve Bank of Australia, a Professor of Economics at Macquarie University, and is currently a Senior Fellow at the Lowy Institute, Sydney. From 2016 to 2021 he served as economic adviser to Myanmar’s democratic government led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Following the military coup that took place in Myanmar in February 2021, Sean was imprisoned alongside Myanmar’s democratic leadership. After 650 days of incarceration and severe ill-treatment, he was finally released in November 2022. Sean has written extensively on macroeconomic policymaking, economic reform, and the role of financial institutions in economic development, with a special focus on Australia, Myanmar, and the Indo-Pacific.

Melissa Crouch

Melissa Crouch is Professor in the School of Global and Public Law, Faculty of Law & Justice, UNSW Sydney. She was one of many people in Australia who campaigned for Sean's release.