Margaret Atwood's prophecy: how fiction merged with fact in the time of Trump

Thirty-five years after writing The Handmaid's Tale, the Canadian author is set to release its sequel. Once again, she has been inspired by "the world we've been living in".

To cross from the US into Canada can currently feel more like entering an adjacent universe than traversing neighbouring lands. The border serves both as geographical demarcation and ideological boundary, the contrasts between Donald Trump's America and Justin Trudeau's Canada representing a broader global divide. Yet in the two years since Trump took the presidential oath of office, it is not the telegenic Canadian prime minister who has become the face of north-of-the-border resistance, but one of his septuagenarian compatriots. Much like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the 85-year-old US Supreme Court justice, Margaret Atwood has been repurposed as a gangsta feminist.

"I am the best they can do?" she exclaims when we meet in Toronto, close to the well-to-do downtown neighbourhood she lives in. We're across the road from her alma mater, the University of Toronto, which houses her archive: a 575-box collection that includes the drafts and typescripts of her 16 novels, 17 works of poetry, 10 non-fiction works, eight children's books, one graphic novel, and the research materials used to write them. "What's wrong with this picture?" she asks sardonically. "I'm not up to the job. I'm too old."

As she peels off her lavender-coloured winter coat, a garment which brings to mind the poet Jenny Joseph's much-loved line "When I am an old woman I shall wear purple", I recount what happened the night before. Presenting myself at passport control at Toronto airport as a journalist, I was asked rather officiously by a young female border agent to declare the specific purpose of my visit. "I have come to interview Margaret Atwood," I said. Instantly a look of unblinking delight appeared on her face, an expression, it seemed, both of patriotism and sisterhood. Then I was whisked through the arrivals halls, as if I myself were a VIP. "Don't tell any terrorists that," Atwood deadpans, as she takes her seat without unzipping the slate grey puffer jacket she is wearing under her overcoat.

Of this Atwood revival, the 79-year-old is characteristically offhand. She's too Canadian to succumb to the narcissism of the age, and, as she will remind me repeatedly over the course of our conversation, too old. "I don't think it's me," she says. "It's the book, the show."

The book, of course, is The Handmaid's Tale, her imagining of a near future where the US has become Gilead, a totalitarian theocracy in which a toxic brew of misogyny and environmental degradation have created a society where the few women capable of bearing children are enslaved by religious elders. The show is its television adaptation starring Elisabeth Moss as Offred, the book's narrator, whose name is a conflation of her male owner, Commander Fred Waterford, and the possessive preposition "of".

Since the series first aired in April 2017, the handmaids' distinctive bonnet caps and hooded cloaks have become as much a symbol of the Trump years as the pink woolly pussy hat. This feminist protest uniform has been worn on Capitol Hill in Washington during Brett Kavanaugh's Supreme Court confirmation hearings, in Britain during the visit of Donald Trump, in Ireland and Argentina, and outside Parliament House in Brisbane by women campaigning for the legalisation of abortion. Modern-day activism increasingly comes cloaked in crimson. The rise of the #MeToo movement has given it added applicability.

You can see why it's useful...They're instantly recognisable. People can't kick you out because you are not creating a disturbance. You are not saying anything. That's the point. And they can't accuse you of being immodestly dressed. You are so modestly dressed nobody can see who you are.

A foreshadowing of this cultural phenomenon came at the US Women's March in January 2017, the day after Trump took the oath of office. As protesters inundated the National Mall in Washington, some brandished placards reading: "MAKE MARGARET ATWOOD FICTION" and "THE HANDMAID'S TALE IS NOT A BLUEPRINT". Atwood herself participated in the Toronto iteration of the protest – "Nobody did anything that was like marching," she recalls, "because there were too many people there" – and I ask whether she participated with a sense of pregnant anticipation, knowing the television juggernaut was about to come over the horizon.

"No," she says determinedly, her tone now less frivolous. "I thought that on November 9 [2016, the morning after Trump's unexpected victory]. And so did everybody in the show, because they woke up that morning and said to themselves, 'We're now in a different show.' Nothing about it changed, but the frame changed." The conversation would be very different if Hillary Clinton had won, I say.

"The conversation would be very different if Hillary Clinton had won," she affirms. "We'd be saying, 'Look what you narrowly avoided.' "

This grand dame of letters is endearingly down to earth. But even dressed in skin-tight leggings and maroon trainers, she still has something of a courtly bearing. Though known for foretelling the future, it is easy to visualise her in a previous age. As a character in a Jane Austen novel, perhaps – a much-loved, if occasionally cutting aunt, taking careful note of every detail and social nuance. Or as the subject in a painting by Vermeer, whose brushwork would capture her sharp features, arched eyebrows and near porcelain skin.

As the low winter sun streams through the window of the hotel suite, it gives her wispy grey hair a halo-like effect. This brings to mind how The New Yorker described her in a profile published on the eve of the television series: "The prophet of dystopia". It is a sobriquet she hates. "I'm not a prophet," she shoots back. Rather, The Handmaid's Tale is rooted in the historical here and now.

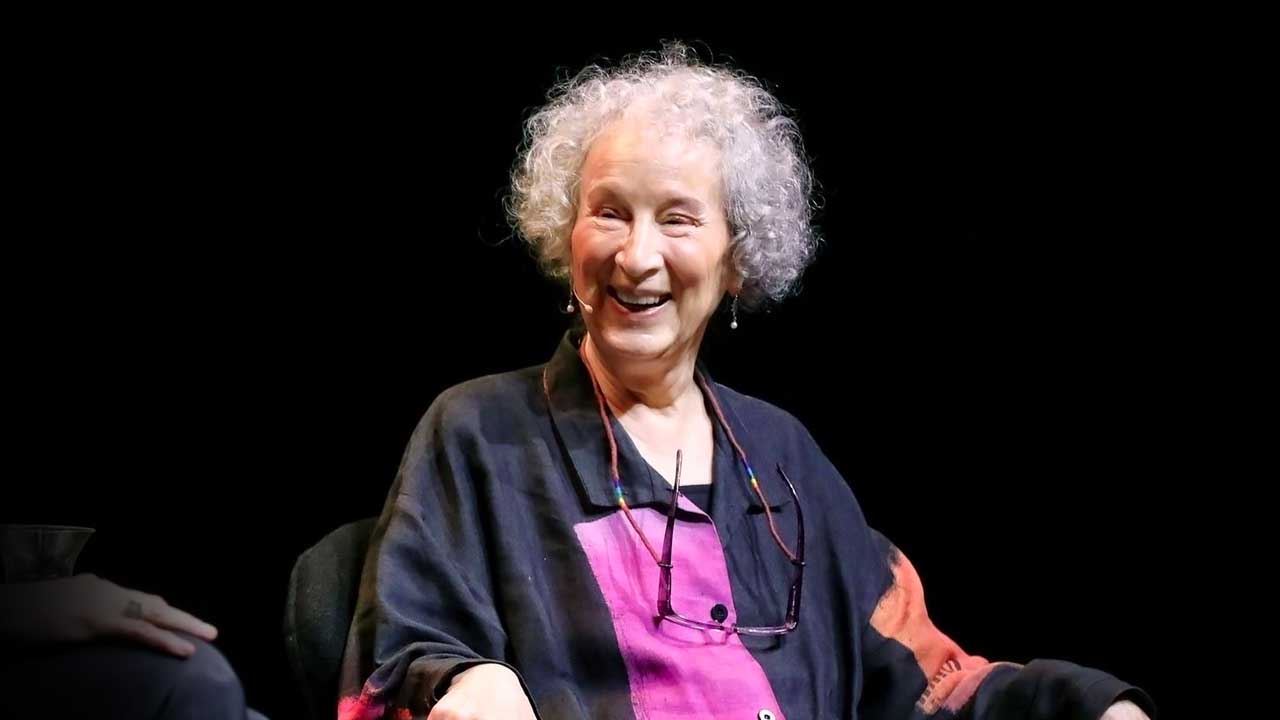

Margaret Atwood speaking at the Sydney Opera House, March 2019, photo by Prudence Upton

Margaret Atwood speaking at the Sydney Opera House, March 2019, photo by Prudence Upton

First on yellow legal notepads, then on an unwieldy German typewriter, Atwood wrote much of the novel in West Berlin, a haven of freedom encircled by a concrete wall and buzzed each week by East German warplanes. "It was on their schedule to make a sonic boom every Sunday to remind everyone they were there," she recalls. "It was that era of Checkpoint Charlie and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley's People."

It was 1984, a year redolent with Orwellian overtones. Her Canadian passport granted passage behind the Iron Curtain and enabled her to experience totalitarianism first-hand. In Poland, she met dissident writers. In what was then Czechoslovakia, she remembers a bellboy pointing silently up to a chandelier in her hotel room where a microphone was concealed.

Her opus was published early the following year at a moment in history, before glasnost and perestroika, when the US was a beacon of democracy and its president (Ronald Reagan at the time) doubled as the leader of the free world. "A lot of people in Europe didn't believe it when it came out, because they didn't want to," she says of her novel. "America was viewed as the shining light, the home of the free."

The response in the US was sceptical, too. "No shiver of recognition ensues," wrote the novelist Mary McCarthy in her review for The New York Times, dismissing any parallels with the rise of the Moral Majority, a Christian right-wing pressure group that had grown in prominence during the Reagan years. "The book just does not tell me what there is in our present mores that I ought to watch out for unless I want the United States of America to become a slave state something like the Republic of Gilead."

"They couldn't believe it because they didn't know much American history," Atwood says of the sceptics. "They couldn't believe that would ever happen in the US, though it already had." To emphasise her point, she adopts a slow stage whisper. "Several times, in several ways." From the fundamentalism of the Pilgrim Fathers to the modern-day religious right, the puritanical streak provides an unbroken thread of American history. Among the many dog-eared newspaper clippings Atwood used for research was an Associated Press report on a contemporary religious sect in New Jersey where wives were labelled "handmaidens". In speculating about this dystopian future, she was jogging the American memory, reaching back to what she calls its "foundational platform of 17th-century theocratic totalitarianism".

Likewise, the notion of Canada as an asylum is an historical perennial, and in The Handmaid's Tale liberty for the enslaved women of Gilead is found north of the border. "Canada has always been the place where people escape to when things go pear-shaped in the US," Atwood says, from slaves via the secret routes and safe houses of the Underground Railroad to draft dodgers during the Vietnam War to current-day refugees fearful of deportation. "The spirituals talk about crossing the river and entering the Promised Land," she says. "That was Canada."

Yet readers who interpret the book as an anti-American screed are mistaken. "It's a pro-American book in a way, because it's saying, 'You're better than this. Don't go there.' If I had completely written off America, I wouldn't bother, would I? It's one of those books you write if you think there's a hole in the road up ahead. If you want people to fall into the hole in the road, you say nothing. If you want them not to fall into it, you say 'There's a great big hole in the road over there. Don't fall into it.'"

Was it the act of a loving neighbour, I ask. "I would say," she nods.

Nineteen Eighty-Four by Orwell was a 'Don't go there' book. All of those are 'Don't go there' books.

Even if the novel was not met with universal acclaim, it quickly became a modern-day classic. As well as being short-listed for the Booker prize, it won the Governor General's Award, Canada's highest literary prize, and also the Arthur C. Clarke Award for science fiction – although Atwood prefers the term "speculative fiction". Hollywood snapped up the movie rights, although casting an actress to play Offred in Harold Pinter's screen adaptation was unexpectedly difficult because so few female stars wanted to be involved in the project (eventually, the British actress Natasha Richardson took the part). The film premiered in 1990, a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The dominant global narrative was the triumph of liberal democracy, what the academic Francis Fukuyama described in his seminal 1989 essay as "The End of History", which provided the thesis for his best-selling book. So it defied rather than defined the zeitgeist.

The backstory of the television series she likens to a saga from the pages of J.R.R. Tolkien. "Everything is in Lord of the Rings. The rights were attached to the original film, then the original film was sold to a distributor, then the distributor went bankrupt and the rights were dispersed and fell into a swamp, and were picked up by a hobbit called Gollum who went into a dark mountain, and nobody knew who had the rights. We didn't know where they were. But finally somebody did a sleuthing job and lo and behold it turned out to be MGM."

The studio approached Hulu, an internet streaming platform with ambitions to rival Netflix. "Hulu went for broke," says Atwood. "They didn't even do a pilot. They went straight to full production." A blockbuster success, The Handmaid's Tale, broadcast in Australia on SBS, quickly scooped up eight Emmys and became the first show on a streaming service to win the Golden Globe for best television series.

Atwood much preferred it to the film, whose director, she says, decided in post-production not to use a narrator. "I'm very glad they used voiceover for the Offred character. Otherwise you watch a person saying nothing for quite a long time. In a totalitarian society, your best defence is silence."

Atwood even had a brief cameo, a scene in which she slapped Elisabeth Moss violently across the face. "Isn't that funny?" she says of playing a baddie. "There weren't many parts for old ladies. I could have been a street cleaner or something."

Popularised anew, the novel has sold an additional three million copies since the television series first aired; it has now sold well over eight million since publication. It has been likened to era-defining classics such as John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, which chronicled the misery of the 1930s Great Depression, and Arthur Miller's The Crucible, an allegory for McCarthyism. For all that, Gilead's theocracy hardly mirrors America's Trumpocracy. Surely that is a fake comparison. "We're not there yet," she says. "As I say to people in the US, if we were really in The Handmaid's Tale I wouldn't be here, and you wouldn't be listening to me. So let's be serious about this; it could be a lot worse."

What about the thrice-married occupant of the White House, the former playboy who became president? "He would not be in Gilead at all. He would have to pious up a lot. There might be Trump-like characters behind the scenes in Gilead, but I don't think he's capable of dressing up pious and uttering piousities in that way." Vice President Mike Pence, a devout evangelical, "is more like the real thing," she says. "How could he be so novelistic? It's embarrassing."

Just as HBO's Game of Thrones has outstripped George R.R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the television series has stretched beyond Atwood's narrative arc. "That's what happens with this kind of television," she says, phlegmatically. Her own next instalment of the story, The Testaments, is due to be published this September, although under the ground rules for the interview I am barred from discussing it – a prohibition which seems to contravene the spirit of the book. "You can ask me, but I just won't tell you anything, except that they do have a cover. They'll draw the curtains on the cover at a time they deem appropriate."

The only details Atwood has so far disclosed is that the sequel is set 15 years after Offred's final scene in The Handmaid's Tale and features three narrators. "Dear readers: Everything you've ever asked me about Gilead and its inner workings is the inspiration for this book," she wrote to her fans when she announced the book last November. "Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we've been living in."

The Testaments promises to be an even splashier literary event than when it was decided, controversially, to release Harper Lee's Go Set a Watchman. Billed as the sequel of To Kill a Mockingbird, its publication was not just anti-climatic but spoiling, because it portrayed crusading lawyer Atticus Finch as a bitter racist. "Is it a mistake to try this?" Atwood asks. "Time will tell."

Centre for Ideas director Ann Mossop interviews Margaret Atwood, March 2019, photo by Prudence Upton

Centre for Ideas director Ann Mossop interviews Margaret Atwood, March 2019, photo by Prudence Upton

Margaret Atwood is a vivid conversationalist with an intellectually promiscuous mind, so the discussion zigzags constantly. From the architecture of Mayan temples, where successive pyramids are layered on top of smaller ones – a mode of construction that sounds usefully metaphoric in the hands of a novelist – to the salt marshes of Norfolk, where she lived during a spell in Britain because it was a favoured haunt of fellow bird watchers. From the royalist leanings of some of America's revolutionary founding fathers, including Alexander Hamilton – "Who'd have thought you take this guy best known for a fiscal system and make this quite amazing musical out of it?" – to how Charles Dickens published his novels episodically, which she views as a forerunner to box set streaming. From John F. Kennedy's "Ich bin ein Berliner" gaffe – "I am a jam-filled doughnut," she laughs – to Joh Bjelke-Petersen's "Deep North" Queensland.

Her connection with the Sunshine State comes from her second husband, the novelist Graeme Gibson, whose father emigrated there from Canada in search of a friendlier climate and cleaner air. "Every time we got invited to Australia we would go up to Brisbane to visit the rellies," she says, laughing. "His mother and his grandmother were from there." She speaks with great tenderness of the man who has been her partner since the early 1970s, diagnosed in recent years as showing the early signs of dementia – she once described him as the husband every novelist should marry. The couple have a daughter, Eleanor Atwood Gibson, who is now in her early 40s.

Unexpectedly well versed in things antipodean, Atwood kept a distant eye on the "Ditch the Witch" misogyny aimed at then Labor prime minister Julia Gillard – "That witch imagery does come up a lot. It's very strong in the anti-Hillary stuff" – but does not look on Australia as some patriarchal pariah. "Compared to a lot of countries in the world, it's Persil-clean," she reckons. "If you think Australia is the worst, then have a look around." Certainly it has progressed since the late 1980s, when she completed a three-month writing residency at the University of Sydney, during which she completed the novel Cat's Eye, her follow-up to The Handmaid's Tale. "I asked, 'What stage are you at?'" she tells me, recalling her hook-ups with local women's groups. "And they said, 'We're at the screaming stage.'"

For all her loquaciousness, she is reticent when it comes to talking about herself. Over the years, profilers have played what's become something of a literary parlour game, treating her as a puzzle that needs to be solved, trying to locate the key that unlocks her personality and writing. However, the novelist – whose puffer jacket has remained zipped throughout, as if to provide an extra layer of protection against probing lines of questioning – finds this kind of psychiatric portraiture tedious. "There's no key," she says emphatically. "Everyone has a lot of contradictory parts about them, and everybody, when you start digging, has hidden parts to their story that aren't immediately obvious."

The geographic isolation she experienced as a child, when her entomologist father transplanted the family into the wilderness of northern Quebec to study insects, meant she lived much of her early life in her imagination. "Up to a point, yes," she concedes, "but you scratch any writer and you find a childhood. Everyone has had a childhood."

Her mother, a dietitian from a family of female high achievers, made sure Atwood and her older brother, Harold, kept up with their studies and reading. By the age of six, Margaret had composed her first poem. Aged seven, she wrote her first novel. "It was a real illustration of how not to write a novel, because it was about an ant, and ants don't do anything until they have legs," she remembers. "Not until the very end did anything actually happen. It's a little like Tristram Shandy." In her teens, Atwood declared that she would pen the Great Canadian Novel.

World War II was also developmental: Atwood was born in November 1939, less than three months after Hitler's tanks rolled into Poland. "I read all of Churchill's books. I knew people who were in the war. And we were Hitler's children. So I was always very interested in totalitarian regimes, and how they come to be."

In the early 1960s, after gaining an English degree from the University of Toronto, she enrolled in graduate school at Harvard, which she reminds me was founded in 1636 as a seminary to train Puritan ministers – the streets of Gilead were based on Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard's home. There, she studied under the intellectual historian Perry Miller, who pioneered the study of American puritanism, which also brought her family history into sharper focus. The Handmaid's Tale is dedicated to Mary Webster, or Half-Hanged Mary as she is known in family lore, a forebear purportedly accused of witchcraft in the 17th century by the Puritan townsfolk of Hadley, Massachusetts.

During her spell at Harvard, Atwood self-published her debut collection of poetry, Double Persephone. A follow-up anthology, The Circle Game, earned her the Governor General's prize. Her first novel, The Edible Woman, an exploration of gender stereotypes seen through the eyes of a female protagonist, was also a breakthrough work. It was published in 1969, but written five years earlier, and Atwood describes it as a work of proto-feminism that anticipated some of the themes, such as female body image, which animated the women's liberation movement. She was not yet 30 when the novel appeared, and it singled her out as one of the most urgent female voices of her generation.

Obstreperously independent, she resists being pigeonholed, a form of intellectual straitjacketing. "I don't have a doctrinaire set of ideas. It's very annoying to some people. I don't think you can be a novelist and have a doctrinaire set of ideas. You are just going to write propaganda." Even the term "feminist" irks her, because it lacks the forensic precision of her prose. "There are so many different kinds of feminists, which is why I refuse to answer the question, 'Are you a feminist?' You have to say, what kind? Are you the 'equality now' kind of feminist? Absolutely. Are you the kind of feminist who thinks all male babies should be killed, apart from 10 per cent? No, I'm not that kind. But there are some."

A natural-born outlier, she revels in being contrarian, an adversarial streak that found expression in a column published in January 2018 at the height of the #MeToo movement. "Am I a bad feminist?" it asked. The question was not part of some late-life crisis or bout of self-recrimination. Rather, her polemic published in Canada's Globe and Mail newspaper defended the controversial stand she had taken when a professor at the University of British Columbia was fired following allegations from a woman of sexual misconduct, a charge the professor denied. Atwood had signed a letter complaining that the university had rushed to judgment by firing Steven Galloway without due process and fair treatment.

It seems that I am a 'Bad Feminist'...I can add that to the other things I've been accused of since 1972, such as climbing to fame up a pyramid of decapitated men's heads – a leftie journal – being a dominatrix bent on the subjugation of men – a rightie one – complete with an illustration of me in leather boots and a whip, and being an awful person who can annihilate – with her magic White Witch powers – anyone critical of her at Toronto dinner tables. I'm so scary! And now, it seems, I am conducting a War on Women, like the misogynistic, rape-enabling Bad Feminist that I am.

Later in the piece she wrote, "The #MeToo moment is a symptom of a broken legal system." Women denied a fair hearing through institutions were turning to the internet instead. But this carried risks. "Understandable and temporary vigilante justice can morph into a culturally solidified lynch-mob habit," she argued, "in which the available mode of justice is thrown out the window."

The backlash was instantaneous. "Wish Margaret Atwood would get back to writing dystopian fiction about a misogynist world instead of, y'know, ACTIVELY CREATING IT," blasted one critic on Twitter. "Actually, Margaret … with all due respect, this isn't what I meant by Bad Feminist," tweeted the author Roxane Gay, who had written a seminal essay under that title.

Atwood, who has almost two million followers on Twitter, initially fought back before abandoning social media for a while. "Taking a break from being Supreme Being Goddess, omniscient, omnipotent and responsible for all ills," she wrote. "Sorry I have failed the world so far on gender equality. Maybe stop trying?"

Was she taken aback by the hostile reaction to her op-ed?

"No, of course not," she says. "I'm not shocked about anything. I'm too old to be shocked."

Was she wounded?

"I don't get wounded by those kind of things. I'm too old. I also know what people are capable of."

And it almost goes without saying that she remains unrepentant. "I was right," she says, deploying that stage whisper again. "You're either in favour of the universal declaration of human rights or you're not. And if you aren't, you're also throwing out the women's rights that go along with that. Universal women's rights."

As she had written in her lightning-rod column: "My fundamental position is that women are human beings, with the full range of saintly and demonic behaviours this entails, including criminal ones. They're not angels, incapable of wrongdoing. If they were, we wouldn't need a legal system."

So Margaret Atwood is increasingly seen in split screen: the clairvoyant gangsta feminist on one side; an ageing heretic, out of touch with more militant strains of feminism, on the other. Ever the outlier, ever the questioner of prevailing schools of thought, she does not seem fazed by these contradictory views. It comes with being shoulder-deep in this modern-day boiling cauldron.

Audience at the Sydney Opera House, March 2019, photo by Prudence Upton

Audience at the Sydney Opera House, March 2019, photo by Prudence Upton

Atwood was in Sydney in early March for a one-off talk organised by the Centre for Ideas at the University of NSW. After the event was announced, the Concert Hall at the Opera House sold out in less than 45 minutes. This ticket rush is a measure of her worldwide renown. So, too, are some of the recent additions to her personal collection of "weird Handmaid's Tale stuff", as she calls it. The bottle of champagne dressed as a handmaid, sent by her British publisher. The memes of First Lady Melania Trump's crimson holiday decorations at the White House. "The Christmas trees are in there," she says, laughing. "It took the internet about five minutes to put bonnets on those trees."

"The irony is," I suggest, "you've had a Trump bump." "Huge," she smiles. "There's no question. I feel very guilty about it. If I had my choices, I would say, 'Spare me the Trump bump and let it be so that things were different.' That isn't what happened, and we have not heard the end of that story yet. He didn't run on an anti-women platform. He didn't run on that. He ran on a bunch of other issues, but that is a subtext and it's a subtext for each and every one of the authoritarian regimes that have come in around the world. Many things are different about them. Their reasons for winning are different. But what they have in common is that they all want to roll back women's rights."

Has this given you a new lease of literary life, I ask. "No," she says firmly. "I already had a literary life and it had not faded from view. The difference is that it was once people who had read the book, and now it's a lot of other people who haven't read the book but who have seen the show. But then they go back and read the book."

She takes special pleasure in knowing that so many younger readers have now been exposed to Gilead, and been galvanised by the experience. "This is not the Me Generation any more. They are not just focused on themselves. They are focused on the wider scene."

When our conversation draws to a close, Atwood levers on her purple overcoat again and steps out into the Canadian cold, while I head back to Toronto's Pearson International Airport. There, US border agents are permanently stationed to check passports before passengers are allowed to board flights southward. A shaven-headed immigration official with beefy, tattooed forearms looks at my journalist's visa and asks what brought me to Canada.

"I was interviewing a Canadian novelist," I say, careful not to mention her name. Without further inquiry, he motions for me to proceed – to cross North America's great continental divide.

This article was published in the Good Weekend, 16 February 2019. The use of this work has been licensed by Copyright Agency except as permitted by the Copyright Act, you must not re-use this work without the permission of the copyright owner or Copyright Agency.