The Future of Justice

Part of the challenge I think is for us to rise above the purely individuated, aggregative consumerist idea of the common good towards something higher, more reflective, something more about learning and persuading and educating and elevating our preferences rather than simply adding them up and trying to maximise their satisfaction.

Humans have disagreed about the idea of justice for millennia. But as we confront a world of uncertainty and disruption, with rising inequality, anger and polarisation, it has become difficult to talk about big questions like justice and fairness, or success and failure. In the past, we might have looked to religion or philosophy to help us think and act. If we want to create a more generous and inclusive public life, can we still look to these domains for answers?

In this talk, hear philosopher Michael Sandel, theologian Rowan Williams and author/filmmaker Mary Zournazi explore what concepts like gratitude and grace mean for us as individuals and societies, and how humility and love may serve us in our relationships with each other. Instead of separating secular and theological approaches, what ideas can we bring together to chart a course for the common good and a more just world?

To delve further, explore Michael Sandel’s recently published book, Tyranny of Merit – What’s Become of the Common Good and Rowan Williams and Mary Zournazi’s Justice and Love – a philosophical dialogue.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and UNSW Arts, Design & Architecture as part of Social Sciences Week.

Transcript

Ann Mossop: Welcome to the UNSW Centre for Ideas podcast, a place to hear ideas from the world's leading thinkers and UNSW Sydney's brightest minds. I'm Ann Mossop, Director of the UNSW Centre for Ideas. The conversation you're about to hear, The Future of Justice, is between philosopher Michael Sandel, theologian Rowan Williams, and author and filmmaker Mary Zournazi, and was recorded live. I hope you enjoy the discussion.

Mary Zournazi: Thank you Ann, and it's been just a wonderful pleasure to have my friends here. Rowan and Michael Sandel. And what an honour to be able to talk to you about the future of justice, two incredible philosophers and theologians of the world. I wanted to think about what some of our ways of thinking about the future of justice might be and it comes together, I think, with the works that, Michael, you have done, and most specifically, The Tyranny of Merit: What's Become of the Common Good? And Roland and I some of our work in Justice and Love, I think there's really interesting crossovers, ways of thinking about philosophy and theology, and also thinking about that space of the public, the space of people's disenfranchisement, the political mistrust that people have, but also how it works at a very individual level too, that sense of loss of dignity, how do we recreate that sense of dignity? And I'm thinking that one of the key elements for us, I think, is this notion of belonging, you know, what, what it, kind of, means to belong. And personally, I've been interested for a long time in different, sort of, theological, philosophical, and also spiritual questions. And most recently, I was listening to, actually, a lecture that was given by a notable theologian, conscious thinker, and at the end of this talk, which was all about, sort of, peace and justice, and all of these things, an audience member, kind of, asked a question, and it was, well, what about politics? And the speaker was trying to, sort of, grasp at you know, how they could answer this question about what about politics? And then I think the audience member was becoming more and more frustrated. And she said, but what about Trump? And then there was still no sense of how these notions of awareness and consciousness could lead to any sort of change. And I guess I want to open up our crossovers and concerns and perhaps curiosity in our works to Michael, first off, which is coming off this tail end about what about politics? And I think, the Tyranny of Merit has this very rigorous discussion about having to think about what merit means today, this idea of success, which has led to a, kind of, political machination that's created these vast divides amongst people. And you've said, and I like, I really liked this because I think it's something we will explore throughout that merit forces out grace. And maybe we could just start there, and then we'll move from there.

Michael Sandel: Well, thank you, Mary, for convening us and Rowan, it's such a pleasure to be in conversation with the two of you on these themes which do connect, just as you say, Mary. The deepest themes and mysteries of theology and philosophy and the human person with very current and pressing political questions. Here's how I see the connection at least, I’d be interested to know what you make of it, you and Rowan. In recent decades, the divide between winners and losers has been deepening, poisoning our politics and setting us apart. This has partly to do, I think with widening inequalities, but not only that, I think it has also to do with the changing attitudes towards success that have come with the growing inequality. Those who’ve landed on top have come to believe that their success is their own doing, the measure of their merit, by implication, that those who struggle, those left behind must deserve their fate as well. This is the dark side of merit or meritocracy. I call it meritocratic hubris. The tendency of the successful to inhale too deeply of their success, to forget the luck and good fortune that helped them on their way. And once we begin to reflect on the role of luck and good fortune, once we stand back from the idea that we are self made, self sufficient human persons, then notions of grace are not far behind. And so in many ways, it seems to me that the resentments that have been created as merit, and notions of self making have gained descendants, those resentments have shown up politically, but they are rooted in this shift in our self understandings.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, and I think that's right, that sense of being able to think that you are your own person without any need for connection, or bond, or belonging. And maybe Rowan, could I get you to maybe reflect on that, because there's lots to tease out here, particularly about political distrust. But just that sense of that role of merit and success in that, kind of, theological sense.

Rowan Williams: Yeah, so this makes a huge amount of sense to me in looking at the kind of culture we increasingly inhabit these days. And behind some of it is what I think is a spectacularly trivialised version of something like Rawls’ political philosophy, as if, you know, we were all actually starting from the same flat, neutral position. And therefore, merit and failure were absolutely straightforward things about the degrees of effort, and the degrees, yes, of worth, or merit and achievement. The fact is, of course, that our history is so much more complex, people always begin with, well, with belonging, as Mary's reminded us. And that belonging shapes the possibilities of choice, shapes the likelihood of moving in one direction rather than another. And there's something in that which ought to remind us that our identity is always already shaped, always already conditioned, not determined, not in a, sort of, flatly mechanical way. But that there is something about our identity, which we did not choose. And that's not very comfortable in our choice obsessed society. So that's one dimension of it, trying to convey to people that sense that they're already implicated, or as the late Julian Rose, liked to put it, invested. People, other factors and other people have invested in my identity, I invest in others long before I've recognised that. And that ought to make us very sceptical about a kind of fundamentalist view of success and failure. Second thing to put in here, I think, is very much at the heart of what Michael's been reflecting on for many years. And that is, what is it in our human relations that we don't ultimately have to earn? Because so much of the attitudes we’re discussing at the moment are about what do you have to do to earn standing security, etc? Now, we sort of know though I think we're slightly losing our grip on it, we sort of know that there are human beings who are not going to be in a position to earn the kind of security and success that we might take for granted. We assume that children need protection, we assume that those with different kinds of ability, need protection, support, and so forth. And yet, somewhere, there's a very clear cut off, which allows us to say, but actually, when it comes to people like you and me, it's everyone for themselves. So I think that that question, what don't we have to earn as human beings, is a key one. And that's where the notion of human dignity, I think, most cashes out, most becomes a pressing an immediate thing. So those are my two first thoughts on this, one is about how I understand my identity, not as my own creation, or triumphant achievement, but as something which is already long before I'm aware of it, a collaborative venture. And the other is this question of, how do I free my social imagination, from that notion that security is something I have to earn, belonging is not something I can take for granted, I always have to be ticking boxes and going through certain kinds of motion in order to count as a member of this community.

Mary Zournazi: And I think that's where actually Michael, some of your talking around the common good has become, if you like more a technocratic, merit oriented good. So that in a sense in your book, Tyranny of Merit, you do talk about this concept of a more consumerist idea of the common good, which is based on these, kind of, ticking of boxes, and then there's one that we would hopefully aspire to, in a different sense would be the civic one. So maybe you could reflect a little bit on that element of that earning, that idea of the earning of success, which has, I think, in your writings too, a long history that does have its roots in some Protestant work ethic. And that's where those interesting tensions lie, I think, with religion and politics.

Michael Sandel: Yes. Well, to begin with the conception of the common good, I think, the predominant conception today of the common good, is a, what I would call a consumerist conception, where the common good consists of aggregating or adding up the individual preferences of everyone, it's a kind of utilitarian conception of the common good. The problem with it is that it leaves unquestioned, unreflected upon those preferences themselves. As against a consumerist conception of the common good, I would argue for what might be called a civic conception of the common good, which depends on living, you know, way of life a shared way of life, in which citizens, all of us, are in are prompted to reflect on what we want, what we care about. On the purposes and ends worthy of us, as a community. So it's a civic conception of the common good in the sense that it doesn't take as given the preferences, as if in a marketplace, that people bring with them initially to public life, but it invites everyone to be open to rethinking, to reflecting on the worthiness of those preferences and how they connect in a common life. So part of the challenge, I think, is for us to rise above the purely individuated, aggregative, consumerist idea of the common good, towards something higher, or reflective, something more about learning, and persuading, and educating and elevating our preferences, rather than simply adding them up and trying to maximise their satisfaction. As for the issue you raised Mary, about the history, the dialectic of merit and grace. One thing that struck me in thinking about the Tyranny of Merit, the book, was, we're focused today, when we think about merit and dessert, mainly about income and wealth and power, who deserves what and why, and how our income and wealth and power, merited or deserved. But an earlier version of this debate goes back to a debate that begins in biblical times, it continues in Christianity and in Christianity, and Rowan will tell me if I'm on the right track here, but seems to me that the debate really was about salvation. Is salvation something that we earn and therefore merit through faithful religious observance, through good works here on Earth? Or is salvation an act of grace, an act of God's grace, a pure, unearned gift? And Augustan took the view very strongly that merit has nothing to do with it, that would impinge on God's power, his omnipotence, salvation is entirely an act of grace, God's grace. But then there's always slippage, that's a difficult view to sustain. Because any religious practice that encourages faithful practice of any kind, tempts the practitioners to read some sense of efficacy into the lives they live, the observances they enact. And so there needs to always be a kind of pulling back, and the reformation, Martin Luther thought that the Catholic Church of his day had slid into the idea, not only with indulgences, but more generally of thinking that it was possible to bend God's favour in our direction. And so he was asserting the gift of grace, Luther, and likewise, Calvin. But then with the Protestants in America, the Protestant work ethic, I should say, with the Puritan work ethic, there was this Calvinist idea of predestination, that's consistent with God's grace, but devoted work and a calling was a sign, a sign of salvation. And this animates the Puritan work ethic. But once the work ethic gets going, it becomes hard not to conclude that devoted faithful work and a calling, is not just a sign, but a source of salvation. So merit comes back in. And it seems to me, I'd be interested to know, Rowan, what you think about this, that there is a consistent tendency for merit, to crowd out grace, at least this seems to be what's happened, if we look over the long course of this dialectic between the two merit and grace. What do you think?

Michael Sandel: Absolutely. It's one of the themes which is already at work, of course, in Hebrew Scripture and the pre Christian period, already there, you have that tension between a liberating act that just establishes people for who they are. So they don't have to be constantly begging God's favour and trying to persuade God to like them. And on the other hand, the much more attractive idea because it's attractive to our egos, that we can genuinely become the sort of people that God could hardly refuse grace too, we are, you know, we're so impressive, right? That God must like us very, very much. And whether it's in the Law of Moses, or in the epistles of St. Paul, there's a fairly consistent needling away at that human tendency to say, well, we must be very impressive if God loves us. It's already there in Deuteronomy, with Moses saying, on behalf of God, do you think it's because you were the most impressive nation on earth that God chose you? No! And St. Paul, in the letter to the Romans similarly, saying to the gentile converts, do you think you have something to boast about over against your Jewish sisters and brothers? No, because it's gift, and therefore your primary orientation is gratitude. And I think one of the themes which you've addressed and which Mary and I have discussed a bit is how gratitude comes into this whole picture, that sense that, again, what I have is not something I have chosen or constructed of myself. And that takes me back, if I can just digress for a moment, to a word you used Michael a few minutes ago, about recognising that we learn in common and civic activity. And it does seem to me that, again, one of the problems in some of our current culture, is that we're very wary of admitting that we learn. It's as if the values and the priorities we have, and the desires we have are all of them given in a single synchronic package. This is who I am, this is what we are. This is where I stand, this is what I want, this is what is owed to me. And this is who we are, we are the land of the free, or the empire on which the sun never sets, or whatever particular myth we go for. And this is just the way we are. And the rest of the world has to get used to it. Just as the rest of the world has to get used to me and my desires. But of course, I have learned to be the person I am. Through a whole range of experiences. We as societies have learned to be the people we are. We have learned values, priorities, we've learned ways of cooperating as well as some of the less desirable things. And something I constantly go back to now when I'm trying to think about political philosophy is how we construct a political philosophy that takes our learning processes seriously.

Mary Zournazi: And can I just, because there's a few things here that I think are really important. And I think the gratitude element takes us into thinking about exchange and gift and relationships with each other quite differently. But there's also an element, Michael, too, where you talk about, you know, this sort of, a civic. And one of the things I think that's important to remember, which is that a lot of people don't even have access to that civic. So in other words, they're not citizens. And I think that Rowan, I think, we've touched on this ourselves in our book, but there is something very important about thinking about in the, kind of, democratic realm that we're thinking through. And that, sort of, anger and frustration happens is the voices that actually aren't heard. And that sense of how do you deliberate? What are the means for that deliberation? I think there is something very crucial in that idea of learning, witnessing grace and gratitude that must come into that sphere that both crosses, I think, an interpersonal, i.e how we respond to each other, but have these tools that we should be doing anyway. But that translation into the biggest sphere of understanding democratic argument in the sense, and I think both of you touch on it, I think, Michael, it's that real concern of the tyranny of merit, that notion of success and rising and mobility, that creates more and more inequality, even though it's based on this assumption of equality, and you talk about it in terms of both Trump and Obama, for instance, both parties, kind of, in some ways use elements of it. And Rowan, you talk about it also, in terms of the tyranny of the majority, the problem of having an assumption that a majority actually means that everybody's in agreeance, and I'm throwing a lot at you, but I think it is, in those crossovers. And I just want to hear both of your comments.

Rowan Williams: I wonder Mary if I could come back on that. Because it's something I've been thinking about a fair bit. What is it that makes a democracy function really, sustainably and justly? Well, certainly, it has something to do with having the right, kind of, questions to put two majoritarian views, to say, well, okay, a majority secures, perhaps a legal shift, it doesn't necessarily secure a moral consensus. And we just have to bear that in mind and work with it. But I'm also very preoccupied with how we create and how we curate, to use the fashionable word, an experience of democracy for people at different levels, how people in all sorts of local and immediate contexts become used to the practices of democracy, that is, to a sharing and learning decision making process. How do people find responsibility together? And one, one example that struck me very forcibly, was on a visit I paid a couple of years ago, to São Paulo in Brazil. I work a little bit with Christian Aid, the development charity, and we support some projects in São Paulo, especially projects for the homeless. I went to visit what had been a hotel in São Paulo and it had been derelict for some years. And it had been taken over by a cooperative of homeless people, helped by the Jesuits social justice program in São Paulo, about 250. families had moved in to this sprawling, semi derelict hotel. And they had basic housing and basic, rather unsatisfactory conditions of public services and so forth. But what impressed me was that they clearly invested a great deal in the meetings they had together to talk about how the place was run. They were very clear protocols about unacceptable behaviour. So that violent behaviour, especially intimidating behaviour towards women, was something which could get you thrown out eventually. They were cooperative arrangements about child care. And I remember that because one of the families I visited there, I think they had four children under five years old living in one room with a couple, the parents, a couple. And I heard a little bit from them about how they organise their childcare, so that it was possible for one of them to work, things like that. The working out, very much face to face, of the conventions that you need in order to keep a community together, the kinds of vehicles you need in order to identify specific needs, and think carefully, and specifically and locally about how they're met. And I thought, well, that that is a project, which is not only about housing the homeless, it's also about giving the formerly homeless some experience of democratic process. And it's experiences like that, that makes me ask, how much of that kind of thing is is available and encouraged and really promoted in communities in our cities, and not only our cities, in our rural areas too, at a time when quite honestly, the assumption is democracy just equals a majority vote, and it doesn't need the education, picking up another of Michael's terms, the education of a political imagination, which shows you what it's like actually to share in decision making. Back to the common good, I'd love to hear Michael more on this. But it seems to me that we've often forgotten the nature of certain kinds of good, which we can't understand, except as common good. Or, to use an example I'm very fond of, if you join a choir, you know that the good of the choir, which you're signing up to, is not the same as your desire to be applauded as if you were singing at La Scala. You have to moderate and adjust your particular skill, your particular strength, so that something emerges, which is deeply satisfying for you and everybody else, and can't just be satisfying for you, otherwise, the entire project collapses. So I take it, Michael, that's part of what you have in mind in thinking about common good and civic good in this sense, the choral models, you might say,

Michael Sandel: Yes. And I liked the example, your example from São Paulo, because what he brings out are two crucial dimensions of democracy. I quite agree that democracy is not only about voting and adding up votes, important though that is, most of the work in the glory of democracy takes place before people arrive at the polling place.

Rowan Williams: Exactly.

Michael Sandel: And two features stand out from the story you just related. One of them is the importance that civic learning be diffused throughout the society, not sequestered in university courses, or in explicit programs of civic education, valuable though they can be. Most people don't go to university. And this is true in most of all of our societies, including in the US and Britain. So if we want to take civic learning seriously, we have to find ways of creating sites of civic education, and reflection and deliberation throughout the civil society, including in workplaces, and in community centres, and in trade unions, and in religious institutions, as well as in universities and schools. The second dimension that struck me about the example you gave Rowan is that the kind of civic education that is diffused and effective out in the world is bound up with practice. Practice in working through common problems, in reasoning together about disagreements. So it's inherently practical, this kind of civic education, which is not to say it need neglect, broader questions of moral and political philosophy of justice, and of rights, and of liberty and the meaning of democracy. But it has to be situated in practice, which is why I very much like the example you offered to connect this to what Mary was raising a moment ago, about the shape of our politics today. One thing that strikes me about it, and this, I think, is part of its hollowness is that the way the mainstream parties in recent decades have responded to rising inequality has not been to contend with inequalities of income and wealth and power directly, but instead to offer a kind of work around, I call it the rhetoric of rising. We heard the slogan again and again, from the 90s to the present, if you want to compete and win in the global economy, go to university. What you earn will depend on what you learn,you can make it if you try. Essentially, working people confronted with for decades of wage stagnation, and job loss, and loss of dignity were told the way out is individual upward mobility through higher education. Go better yourself by getting a university degree, then maybe you too will flourish. Now, in some ways, this rhetoric of rising seems inspiring. You can make it if you try, but it contains an implicit insult. And the insult is this, if you haven't been to university, and most people haven't, and if you're struggling in the new economy, your failure is your fault. And this I think this implicit insult, those who were offered the rhetoric of rising on both sides of the political spectrum, were tone deaf to the insult implicit in what they took to be an inspiring, encouraging message. And they missed the resentments, and the anger, and the insult that they were actually contributing to. And eventually these resentments gathered and mounted and found expression in 2016, with the election of Trump in the United States, in some respects, the vote for Brexit in the UK, the appeal of authoritarian populist figures who railed against elites, credentialed elites, in many democracies. So I think this is what connects an impoverished conception of the common good, an inadequate response to the rising inequality, with the excessive emphasis on meritocracy and credentialism, that even centre left parties have embraced in recent decades.

Rowan Williams: And centre left parties, like some of the right, have bought into this extremely narrow view of education itself, as a result.

Mary Zournazi: Yes.

Rowan Williams: So we have the threat here in the UK, of university courses being assessed by the average income of graduates from those courses, the quality of teaching must be what conditions the level of income that you have. And this seems to be such such a fundamentally dangerous distortion of what education is.

Mary Zournazi: Yes. Can I? I just wanted to reflect on this, because there's something very important about that notion of the insult, and also that role of witnessing and learning. And I think, when it comes to that, disenchantment, I guess, and how to work around it, find ways and tools to actually move beyond it. And I think that there's something in the recognition, the way Michael, I think you have woven this argument around this drive, this notion for success that’s, sort of, overtaken, and both sides of the political sphere have done it. There's something in that, kind of, moment of, okay, this is what has created the inequality, actually, in disguise of equality. But how is it that things like gratitude in a real sense, how is it that notions of grace, it is this idea of the conversation, being able to have those very local conversations, I even think about it in terms here, just to people wanting to get vaccinated. If you're talking to your neighbour, and, you know, they've got all these fear conspiracies about the government controlling their bodies, or you know, whatever, whatever, whatever. But you start to have a conversation, and then that changes the dynamics somewhat. So I'm wondering about getting past the insult, and how, how can we work effectively creating the public space for all different kinds of voices, which as I said before, there are a lot of people who don't even have access to that voice, because they're not students. And just trying to sort of throw that in the mix too, that kind of realm of both, I think Rowan and I have talked about it, I think that doing justice, what are those ways of creating that deliberativeness in that sense of also, imagination and other other means, other ways of bringing our realities together?

Michael Sandel: Well, Mary, I would say that the one place to start is to reimagine the terms of public discourse, to focus less on the rhetoric of rising and to focus less on arming people for meritocratic competition in a market driven society, and to focus more on the dignity of work, on asking, how can we as a society make life better for everyone, regardless of how successful they are at doing well on university entrance exams, regardless how successful they may be at clamouring up a ladder of success whose rungs have been growing further and further apart? How can we enable people to flourish in place, not only to escape their place, this also connects to the earlier part of our discussion about the situated, embedded character of our identities, but it's connected to the dignity of work because it's connected to contribution, and to the social recognition and esteem that comes when everyone feels that they are capable of contributing to the common good, and to win social recognition and esteem for having done so. And this connects Mary with gratitude because, well, here's the concrete example. During this pandemic, we've seen that the inequalities that pre-existed the pandemic had been highlighted most vividly in the divide between those of us who have been able to work remotely, and those who have either lost their jobs, or who, in order to perform their jobs have to expose themselves to risks on our behalf.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah.

Michael Sandel: Those of us working at home, have come to recognise how could we miss, how deeply we depend on workers we often overlook. Not only the workers in health care and in the hospitals, but I'm thinking also of delivery workers, warehouse workers, grocery store clerks, lorry drivers, childcare workers, these are not the best, or most honoured workers in our society. And yet now during the pandemic, we began calling them essential workers, or key workers, and sometimes clapping for them. So this could be an opening for a broader public debate about how to bring their pay and recognition into better alignment with the importance of the work they do. But the key to doing that, politically, is to keep alive the sense of gratitude that we at least glimpsed, it's a perishable thing. But we at least glimpsed this gratitude, during our recognition of our dependence on their contributions.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, absolutely. And Rowan, because I mean, that notion of gratitude in that sense, is really vital, I think, do you want to reflect on that Rowan? Because it's very rich, I'd like to keep pushing out this idea of gratitude.

Rowan Williams: It is a very, very rich theme, I think. And I think Michael has put his finger on one of the things that does make this a very interesting and potentially very significant political moment, if we can have the imagination, and the courage to seize it. And well, the jury's still out, I think, on whether we have the leadership to help us there. But that's another story. But it does seem to be that one of the things implicit in this is, to put it very simply, we may be grateful to other people for any number of things. And to sense our indebtedness to others, across a broad range of skills and gifts, is part of this. So what you were saying, Michael, about the kind of community where everyone feels, there is a level of esteem, a level of acceptance, it's not because they're all doing the same thing, or they're all succeeding in the same way. And the flattening out of that landscape is a real, moral and social loss. It's connected, of course, with some of the ways we think about older people. The sense that well, the over 70s, are intrinsically a drain on society. And we'll try and minimise the drain on society. And we'll try and keep them happy. But there's not very much sense of what the dignity of an older citizen might be in terms of contribution, in terms of providing a sense of anchorage and stability, perspective and experience, that others need. Similarly, in a complex society, there are different kinds of excellence, the excellence of the person who might emerge from a university course with a handsome salary, and a job in a hedge fund management business in the city of London or wherever, alright, that's perhaps one kind of excellence, it's certainly at the very least comparable with the excellence of somebody whose particular courage and skill goes into care working, or indeed, food delivery, and to recognise that all of those are to be valued, and all of those are part of an interlocking system in which our gratitude may, as I say, be offered for a range of things. That's one of the things we have to try and establish, I think.

Mary Zournazi: yeah, and I'm thinking of a German sociologist, Georg Simmel, who talks about gratitude as there's no expectation of a return, you know, like you don't you're not expecting the gift back to you. So it is a, sort of, sense that gratitude is about, you're grateful that this that this occurs, that this happens, that this is possible, and that this, in a sense, I think, activates a more generous or more, well sprung, sort of, approach to living to others, to perhaps something, that for one of a better word, but abundance, that the fear is the scarcity, and of course, with climate change with the economic systems of these kinds of inequalities, because of the ways in which our social organisations have happened, there is a scarcity. But there's not, in terms of real living, there isn't necessarily, there is a sense that we can actually be grateful without expecting a return from it. Which then then makes me think about that notion of success, which I think, Michael, you've also noted that success for the winners can also be wounding and difficult. Just as loss is and failure. And I think there's something in, you know, the reorientation, I think, Rowan, you're right, you know, there is a moment now, if we can really galvanise the sense, as Michael has opened up, that that we are, you know, the needs that we have are changing, and have changed. And we really need to seize the opportunities of discussions like these throughout the world, in a sense, to get that happening, that sense of grace, that sense of gratitude. So Michael, I'm just going to go back to that notion of success there as well.

Michael Sandel: Yes, our excessive emphasis on a certain kind of success, the success bound up with self making and self sufficiency. That way of thinking about success, it's deeply at odds with the notion of gratitude, contribution and reciprocal recognition and esteem that we've been discussing. I agree, Mary, that gratitude is not a kind of one for one exchange. And yet, it can be part of an understanding of the common good, that conceives community as a scheme of reciprocal dependence. Not measured in individual exchanges, but reciprocal dependence nonetheless. We tend to assume, in a market driven society like ours, that the money people make is the measure of their contribution to the common good. But a moment's reflection shows that this can't be right. Even the most ardent defenders of laissez faire, free market capitalism are unlikely to believe this, because it would require belief that what that hedge fund manager Rowan mentioned does, is truly 800 or 900 times more valuable than what a school teacher does, or what a nurse does, or, for that matter a physician. But what we've done is we've outsourced our moral judgement about what counts as a valuable contribution to markets. And so any politics that would renew the common good, would have to take up this question, I think, about what counts as a valuable contribution to the common good. Such a politics would be demanding, because it would require the kind of public discourse that would reclaim from markets, the judgement, the moral judgement…

Mary Zournazi: Yes!

Michael Sandel: About what truly counts as a valuable contribution to the common good, and to deliberate about that is to deliberate about contestable conceptions of the purposes and ends of political community. But I think that would make for a more demanding, but also a morally more robust kind of public discourse than the kind to which we become accustomed.

Rowan Williams: It's very interesting that people are beginning to turn back again to ask questions about what a good human life actually looks like, we need narratives of that.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah.

Rowan Williams: And that's harder work in political discourse than some of the shortcuts we're used to. But without those narratives, which say, look, that's a life you might think, looks worth living. And it's not determined by these mechanical measures of financial success, it's determined by a lot of other things. We might want to talk about what those things are. When you look at that kind of life, what is it that strikes you? What is it that seems enviable, or at least desirable in that kind of life? And that's where I'd also want to say that the life of the arts and the imagination comes in here as profoundly political, in the most important sense, and why saddens me so much to see in the UK, as well as elsewhere, an increasingly dismissive attitude to the role of the arts in society.

Michael Sandel: I agree completely, Rowan, with what you've just said, about how a conception of the good life, the good human life, is indispensable for the healthy, kind of, democratic public discourse that we, we three have been discussing and affirming. But I'd like to put to you an objection that I often get when I say that conceptions of the good life belong at the centre of politics. Because I imagine people listening to us, some of them will wonder exactly this. How do you answer the objection, that we live in pluralist societies, we disagree about conceptions of the good life. We disagree about questions of morality, religion, and faith. And so if you are telling us, or if you three are telling us, that we need a kind of public discourse that addresses among disparate pluralist, democratic citizens, contested conceptions of what it is to lead a good life, how can we possibly surmount the polarisation, which is already ample enough all around us? Isn't that a recipe for a hopeless disagreement? Rowan, what would you say I constantly pressed on this, how would you answer it?

Rowan Williams: I'm constantly pressed on it as well, I have to say. First thing I'd want to say is, frankly, sometimes it's in people's interest to overstate the disagreement that there actually is, to overstate the degree of real moral pluralism, it's very unlikely that you will meet very many people around who will say, for example, that children do not need a safe environment in which to grow up. It's very rarely that you will meet someone who says, the overwhelming bulk of a nation's expenditure ought to be in the promotion of aggressive international adventures and war. It's very rarely that you'll meet people who will say that the stability of human relationships is of no interest or whatever. And I, I note these things, because, on the whole, across the much vaunted moral pluralism of different societies in our world, there is, in fact, a remarkable degree of convergence on some things, some interests and some concerns. There's a recognition, in some ways, a surprisingly strong level of recognition of the need to defend the vulnerable. There's a recognition of the need for cross cultural international collaboration to secure public health. We've seen that in the last 18 months. So that's the first part. I don't think we should exaggerate this. Second, though, all right, so there are very tough disagreements within society, about moral issues, about, let's say, the morality of physician assisted dying, which is becoming a political question again, in the UK. Now, if you assume that the people with different convictions are not simply going to vanish overnight, there is a good you can all agree on, in terms of how to live respectfully with that difference, how to allow for conscientious ways around it, how to allow for continuing debate about certain aspects of it. And that, in turn, becomes an aspect of common good, in a diverse society. So I'm not, I think, disposed to give up on the notion of common good and what you might call the negotiation of a morally manageable society, just because we disagree. On the contrary, it's that disagreement that, if you like, pushes us towards thinking harder and harder about what I call the satisfactory moral management of a society might be, what kinds of conscientious exception you might look for, what kinds of provisionality you build into certain sorts of decision, what kinds of review of certain controversial matters you might want to return to. And above all, what kinds of general provision for the vulnerable overall and also for minorities in particular, you might want to build in to an ongoing democratic system

Mary Zournazi: That actually makes me think very much of the importance of storytelling, actually, within the space of that sense of the public, that the ways people express themselves, whether it be through the local, just, you know, one on one, people's conversations. Whether it's through recording different voices, hearing different voices, understanding different voices. And there's something in that responsibility, I think, we have so it's not only just arts, I mean, it's a culture of, of kind of training of the imagination. But Michael, yeah, the vegetation for you that role in storytelling and discussion in argument.

Michael Sandel: Yes, I think it's part of an adequate account of the human person and of identity depends on, Mary, precisely your emphasis. On the sense in which we are storytelling beings, our lives are constituted by the narratives that enable us to make sense of our lives. And as we reflect on those narratives, we find it almost impossible to conceive ourselves as unencumbered selves, selves so independent that we're unbound by moral or civic ties, antecedent to choice. Storytelling and narrative, pitch us into the kind of reflection that encounters our sense of situation, that encounters our incumbrances. May not embrace or affirm all of the encumbrances that we find, but it's the starting point for critical reflection that can connect us with the wider communities without which it would be difficult, if not impossible to understand what's worth caring about, to understand our purposes and ends, as individuals, but also as members of communities, of our wider society and ultimately, of the humanity we share.

Mary Zournazi: Rowan?

Rowan Williams: Indeed, yes, I agree, we are essentially storytelling beings. And that's to do with the learning thing, once again, understanding how we got to be who we are, and where we are, and therefore understanding that the other person has come to be who they are, and what they are. Listening to that, and within that, also, because every story works like this, recognising the moments of failure, the moments of wandering off the way, and the moment of new beginning. This is why, to state the obvious, I, as a religious person, inhabit and treasure the story that I tell daily, largely because it is a story of failure and new beginning. It's a narrative that doesn't freeze me as the timeless possessor of these desires, skills and wants, but allows me to understand that there's space and there's time for learning and the remaking to happen.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, I mean, one of the things I had, you know, I had thought about talking about was this idea of tragedy and thinking about what we're living through. And Rowan, I know, you've written a lot on tragedy in literature, and in particular, the book that's always fascinated me, is Christ on Trial, you know, how do we stand up when we're in a moment of trial, which I think we are right now. But I guess, just listening to what we've been discussing, there's something also about connecting these ideas of grace. And also, this fundamental idea of love too, not love in a sort of sentimental form by any means. But as a form of alliance and a bonding that actually takes into account perhaps, realises the histories, in which, the stories, in which have been neglected or have been actually effaced from history. And this is where I think the question of dignity, of work, in a sense comes in too, because if we ignore the reality of what has happened over the last four decades, Michael, as you point out, through, kind of, globalisation and a more meritocratic way of governing, then we're losing that real sense of bond and alliance, that actually is the potential that holds us together. And so I think that's where grace and gratitude come back into the equation. It is about our everyday relationships.

Michael Sandel: Yes, and I think part of what our conversation has brought out is the view that the three of us share, that it's not possible to explain our political condition and the anger and the resentment and the polarisation of our politics simply in economic terms. The rising inequality of recent decades is an economic condition that was brought about through certain political choices and power arrangements. But it was changes in attitudes, towards success, and toward the human person, that converted the inequalities of income and wealth into a society of winners and losers. Winners and losers, that's about attitudes, that's about values, that's about self understandings. And this, once we recognize this, and begin searching for alternative ways of conceiving social life and the common good, and the human person, we are led to this richer, moral and spiritual vocabulary of dignity and humility and grace. They’re connected. And one thing that struck me about the conversation we've been having is that we recur to this moral and spiritual vocabulary, even to account, to diagnose what's gone wrong with our civic life. The dignity of work is actually undermined and eroded by a success ethic that conceives ourselves as self made and self sufficient. That imagines that the success of the successful is their own doing. Those who are alive to the role of luck, and contingency, and indebtedness are more likely to be able to achieve a certain kind of humility. Because if we believe, if we really believe, that our success is our own doing, it makes it hard to imagine ourselves, this goes back Mary to imagination, to imagine ourselves in other circumstances, in other people's shoes, but if we are alive to the contingency of our lot, or to the role of luck and fortune in life, or grace, we're more likely to be able to look upon those less fortunate than ourselves and say, they’re, but for the grace of God, or the accident of birth, or the mystery of fate, go I. And so this humility, can bring grace back in, can make it a, kind of, true counterweight or antidote to the excesses of merit. It involves a, kind of, moral and spiritual turning that I think is the precondition for a politics of the common good, that might be, at least, a step away from the harsh ethic of success that drives us apart toward a more generous public life.

Rowan Williams: Indeed, well, I think what's been said is that without some categories, like repentance and conversion, we actually become less human. Because we, as I said earlier, we freeze our sense of ourselves. And freezing is bad for us. We don't respond, we don't empathise, we don't engage. And the sense that people are being encouraged to shrink into those little bubbles of self referentiality. It's a very bad outlook for the health of our political and social future. And I think also of the way in which, you mentioned it, Michael, in the theological tradition, this great tension between merit and grace, that sometimes allowed people like St. Augustine, like Aquinas, like Luther, in certain moods, to say, the point is, that once you realise you have been welcomed, you will have been graced, you realise that you do not have a point of advantage, privilege, unaccountable power over anyone else, you are somehow set free to become an agent of welcome or of grace. Now, you can put that in more secular terms, but the theological language is significant there, if you have been welcomed, you are more likely to be a welcoming person.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah.

Rowan Williams: And St. Augustine is very clear that the problem in unjust, oppressive, and unequal societies is not just the dehumanising of the poor and the powerless. It's also the dehumanising of the wealthy and successful.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, it did make me think of my father too. And I remember because he had been a political refugee to Australia. And I remember when I was a young, you know, as a teenager, you tend to be not interested at all in your parents, and their lives, and their history and all of that. And I think he felt that his work, he became a, sort of, a labourer, but his work wasn't viewed with any dignity, and that we as children, were not treating him with any dignity. And I remember him being really angry at us and saying, you know, you just don't give me any respect, you don't respect. And I think it is to do with being able to recognise the stories of the people that you are with, and recognising those stories, those histories that are part of that recognition, of that welcome, I think, Rowan, that you're talking about. And so, I just would like to say thank you, because it's just been, there’s so much in that discussion that I think hopefully will continue, and people will be able to continue the discussion as well. But I was also imagining the idea of the public space, the idea of imagination. And I've been thinking the last few days, I've been working in the park, because we're all in lockdown here in Sydney, and the park is almost like a square, and it feels like a real public space. Everyone already almost in the whole neighbourhood is out there, physically distancing, of course. But because I'm in a multi ethnic neighbourhood, it's like everybody's there, the kids, the elderly. And it's like, almost, a real, you could imagine this, you’ve got to visually imagine a space too, in which we can all inhabit. And those stories can be told, that those arguments can be held. And I was just thinking when I was in the park, this feels to me like the public space, in this weird moment of COVID lockdown, you know? So there's something potential, I guess, into the future. So thank you. Thank you both.

Rowan Williams: Thank you.

Michael Sandel: Thank you.

Ann Mossop: Thanks for listening. This event was presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas, and UNSW Arts, Design and Architecture, as part of Social Science’s Week. For more information, visit centreforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Michael Sandel

Michael Sandel teaches political philosophy at Harvard University. He has been described as a “rock-star moralist” (Newsweek) and “the world’s most influential living philosopher” (New Statesman).

Sandel’s books, including What Money Can’t Buy, and Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?, have been translated into more than 30 languages. His legendary course ‘Justice’ was the first Harvard course to be made freely available online and has been viewed by tens of millions of people. His BBC series The Global Philosopher explores the ethical issues lying behind the headlines with participants from around the world.

Sandel’s new book is The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? was named a ‘Best Book of 2020’ by The Guardian, Bloomberg, New Statesman, and The Times Literary Supplement, The Tyranny of Merit offers a novel diagnosis of our polarised politics and how to heal it.

Sandel’s lectures have packed St. Paul’s Cathedral (London), the Sydney Opera House (Australia), the Delacorte Theater in New York’s Central Park, and an outdoor stadium in Seoul (South Korea), where 14,000 came to hear him speak.

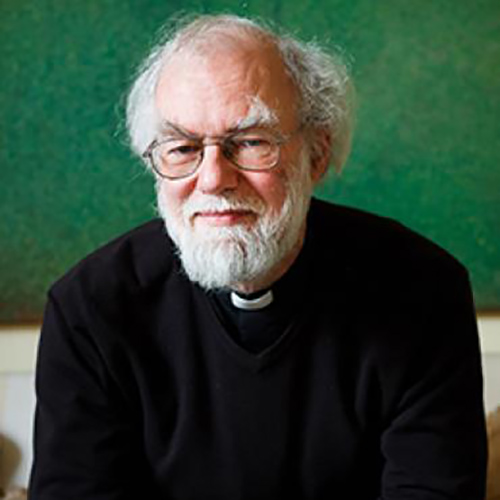

Rowan Williams

Rowan Williams (Baron Williams of Oystermouth) is former Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge (UK). He was formerly Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at the University of Oxford (UK) and was Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 – 2012. Rowan recently co-authored with Mary Zournazi, Justice and Love – a philosophical dialogue.

Mary Zournazi

Mary Zournazi is an Australian film maker and cultural philosopher. Her multi-awarding winning documentary Dogs of Democracy was screened worldwide, and her most recent documentary film, My Rembetika Blues is a story about love, life and music. She is the author of several books including Hope – New Philosophies for Change, Inventing Peace with the German filmmaker Wim Wenders, and her most recent book is Justice and Love – a philosophical dialogue with Rowan Williams. She teaches in the sociology and anthropology program at UNSW Sydney in the School of Social Sciences.

Photo credit Effy Alexakis.